The Workman family plot in Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery is a large one, including six large tombstones engraved with the names of almost 30 people. But William Workman (1807-1878), a successful businessman who served as mayor of Montreal for three years, is not buried there. He was laid to rest alone, in a large mausoleum some distance from the family plot.

Before I started researching the Workmans, a cemetery staff member told me that William had wanted family members to be buried in the mausoleum with him, but they refused. Neither of us knew why, but now I have an idea.

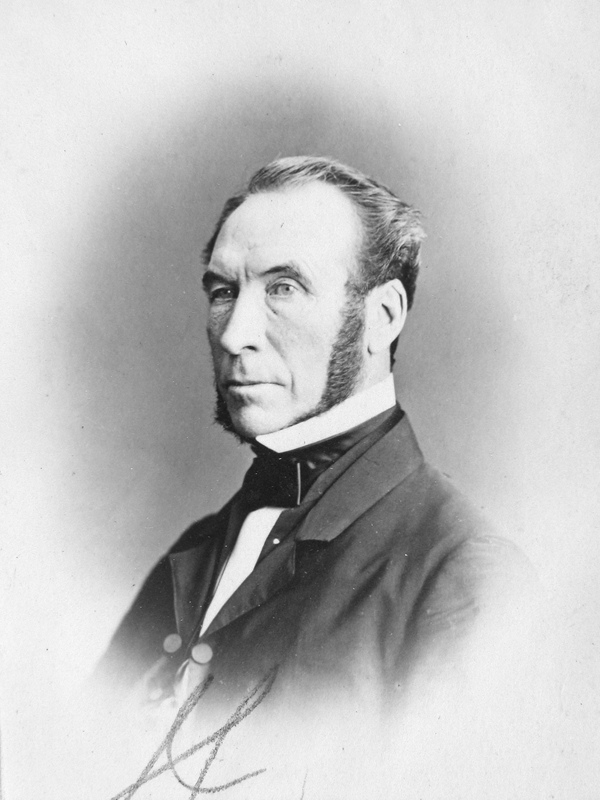

Born in 1807, William was the fifth of nine children. The family lived near Belfast, in what is now Northern Ireland, where his father was a teacher and estate manager. In 1819, William’s oldest brother, Benjamin, immigrated to Montreal. Three brothers followed soon after and, in 1829, the rest of the family moved to what was then Lower Canada.1 Before emigrating, William worked as a surveyor for the Royal Engineers, mapping Ireland for the Ordnance Survey project. In Montreal, his first job was as assistant editor of theCanadian Courant and Montreal Advertiser, a weekly newspaper owned by brother Benjamin. Soon, however, William found his true calling: as a businessman.

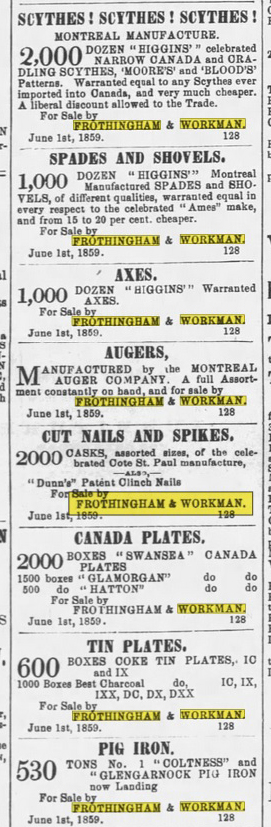

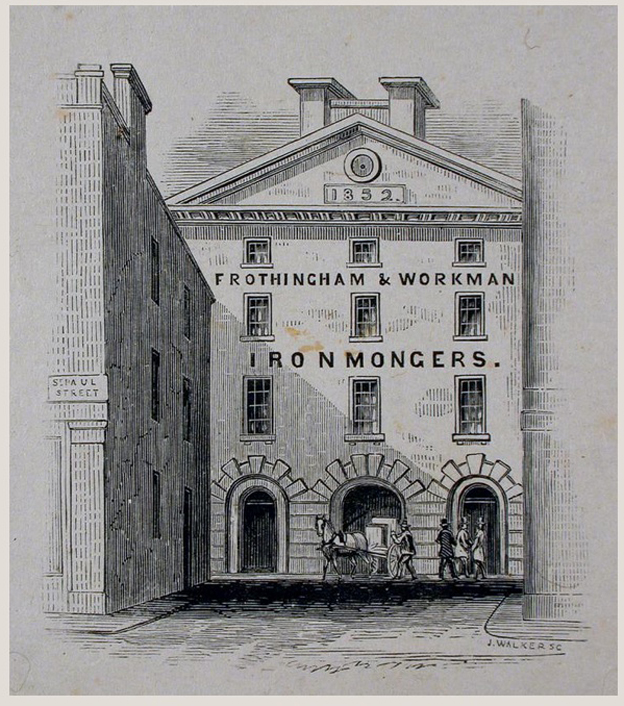

He found employment with a hardware firm, Frothingham & Co., and within a few years he became a partner. As of 1836, the company was known as Frothingham and Workman, and it became the largest wholesale hardware company in Canada, selling scythes, shovels, augers and nails. When William retired from the hardware business in 1859, his brother Thomas took over running the company.2

Montreal was growing rapidly, and William found opportunities to invest in fields such as banking, transportation and real estate. William was elected president of the City Bank in 1849 and served in that capacity until 1874.3 In 1846 he was one of a group of prominent Montrealers who founded the City and District Savings Bank, established to help ordinary people save their money, and he was president of that institution for several years.

William invested in Canada’s first railway, the Champlain and St Lawrence, completed in 1836 to connect Montreal to Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River.4 He was also a shareholder in the St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad, and he collaborated with several other individuals to found the Canadian Ocean Steam Navigation Company in 1854.

Around 1850, he and a business partner became real estate developers. They bought a piece of land south-west of Montreal’s city limits, near the Lachine Canal. The canal attracted industries such as brass foundries and rolling mills, and nearby manufacturing facilities belonging to Frothingham and Workman employed hundreds of people. The partners laid out streets, built sewers and divided the property into housing lots. The area, known as Sainte-Cunégonde, became a village in 1876 and a tiny independent city in 1890, but eventually it became part of the City of Montreal.5 Workman Street, named after William, still exists in the area.

William was also a generous philanthropist. He was president of the St. Patrick’s Society at a time when that organization was involved with both the Roman Catholic and Protestant communities. Later, he supported the Irish Protestant Benevolent Society. In 1864, he helped create the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge, serving as president from 1874 to 1877. He was also president of the Montreal Dispensary and Hospital for Sick Children.

He was not deeply involved in politics, but he was elected mayor of Montreal from 1868 to 1872 and proved to be very popular. This aspect of his life will be the topic of another story.

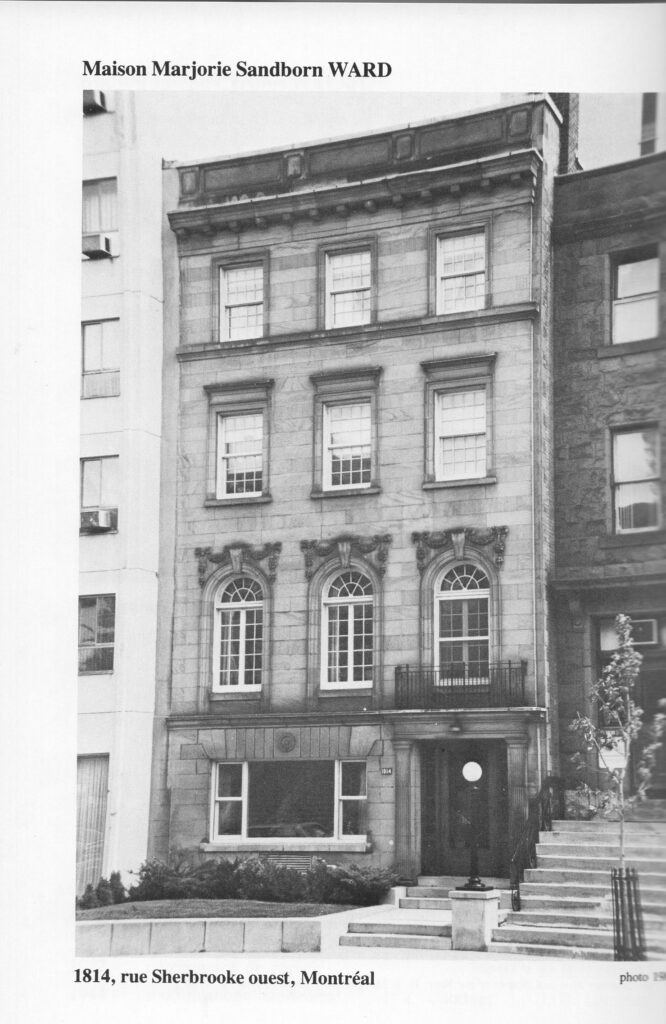

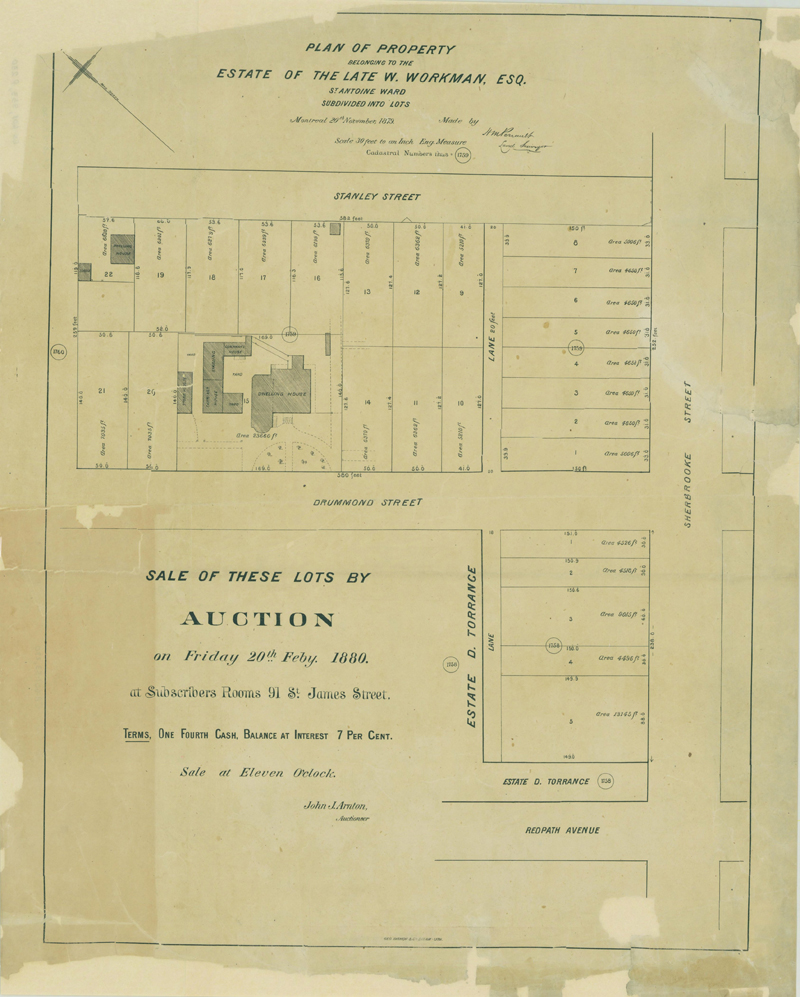

Around this time, wealthy merchants began building large homes on the slopes of Mount Royal, an area that became known as the Golden Square Mile. William bought a full block on the north side of Sherbrooke Street, between Drummond and Stanley, and built a mansion he called Mount Prospect.

William Workman and Elizabeth (Eliza) Bethell were married at St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church on February 10, 1831. Eliza came from the same part of Ireland where William had grown up, so perhaps they had known each other there. They had seven children, so the house should have been full of activity, but it didn’t turn out that way.

It was all too common for children to die young in 19th century Montreal, and William and Eliza lost three little ones. Their firstborn, Elizabeth, was born in December 1831 and died the following summer. Their third child, Emma, was born in August 1837 and died in April 1839. Another girl, Malvina, was born in July 1845 and died in April 1847. Two daughters, Louise (or Louisa) and Elizabeth (Eliza), grew to adulthood, but Eliza, who married Robert Moat, died in 1871. Louisa married Joel C. Baker, a lawyer who went into the hardware business with Louise’s uncle Henry Mulholland. But William found the death of his only son, also named William (1840-1865), the most devastating blow of all. By then, he and his wife may have already been living apart.

An image of the 1861 census suggests that Eliza was not living at Mount Prospect house, but with her married daughter Louisa Baker and her husband,6 so perhaps William and Eliza had unofficially separated by then. In the 1871 census, seven people were listed as living at Mount Prospect, including a cook, a coachman and a horseman. William was the only family member listed.

In a book about William’s brother, The Father of Canadian Psychiatry, Joseph Workman, author Christine Johnston remarked that Joseph did not have a high opinion of William, commenting in his diary that he thought Wiliam had damage in his head, as well as bumps outside it.7 Perhaps William was also concerned about his own mental health: Johnson wrote that William visited a phrenologist in the United States to examine those external bumps. Johnston also noted that family records suggested William was an alcoholic. If true, that might explain the difficulties in the Workman household.

Nevertheless, many people admired him. When he died, Montreal’s English-language newspapers published extensive obituaries, describing William’s many accomplishments as well as the long and painful illness that led to his death.8 According to one newspaper account, some 400 people attended his funeral at St. James the Apostle Anglican Church, and many followed the hearse to Mount Royal Cemetery.

William Workman seemed to have everything, but without his family surrounding and supporting him, his life appears to have been a sad one, and those problems followed him to the grave.

This article is also posted on the collaborative blog https://GenealogyEnsemble.com

Notes

William’s sister Ann (1809-1882), who married hardware merchant Henry Mulholland, was my great-great-grandmother.

Some photos of brother Thomas Workman’s house on Sherbrooke Street are erroneously identified as William’s house. I have not found a photo of Mount Prospect.

There are several photographs of a young man identified as William Workman in the McCord Stewart Museum’s online photo collection. This must the son who died in 1865.

Phrenology was a popular pseudoscience in the 19th century. Its proponents believed that the measurements of the skull were indicative of mental faculties and character traits.

See also:

Benjamin Workman: Leading the Way, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 12, 2025, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2025/03/benjamin-workman-md-leading-the-way.html

“Dr. Joseph Workman, Pioneer in the Treatment of Mental Illness” Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct 26, 2017, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2017/10/dr-joseph-workman-mental-health-pioneer.html

“The Miller of Moneymore”, Writing Up the Ancestors, May 14, 2025, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2025/05/the-miller-of-moneymore.html

“Henry Mulholland, Hardware Merchant”, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 17, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/03/henry-mulholland-montreal-hardware.html

Mulholland Bros. Hardware Merchants, Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 15, 2025, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2025/01/mulholland-bros-hardware-merchants.html

“The World of Mrs. Murray Smith”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Feb.24, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/02/the-small-world-of-mrs-murray-smith.html

Sources:

1. Christine Johnston. “The Irish Connection: Benjamin and Joseph and Their Brothers and their Coats of Many Colours,” CUUHS Meeting, May 1982, Paper #4, p. 2.

2. John Frothingham, Obituary. The Portland Daily Press, May 24, 1870, p. 3. Newspapers.com, accessed Jan. 5, 2026.

3. Nicholas Flood Davin, The Irishman in Canada, London: S. Low, Marston, 1877, p. 334, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/irishmanincanada00daviuoft/page/334/mode/2up accessed Jan. 5, 2026.

4. G. Tulchinsky, “Workman, William,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/workman_william_10E.html accessed January 5, 2026

5. Olivier Paré, “Les bâtisseurs de la Petite-Bourgoyge” Encyclopédie du MEM, https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/memoiresdesmontrealais/les-batisseurs-de-la-petite-bourgogne5 accessed Jan. 5, 2026.

6. Ancestry.ca, 1861 Census of Canada. entry for Joel C. Baker, Canada East, Montreal. Library and Archives Canada, Canada East Census, 1861, p. 4210. accessed Jan. 6, 2026.

7. Christine I. M. Johnston, The Father of Canadian Psychiatry: Joseph Workman, Victoria: The Ogden Press, 2000, p. 122.

8. “Late William Workman”, The Gazette, Feb. 25, 1878, p. 2. Newspapers.com, accessed Dec. 30, 2015.