written in collaboration with Justin Bur

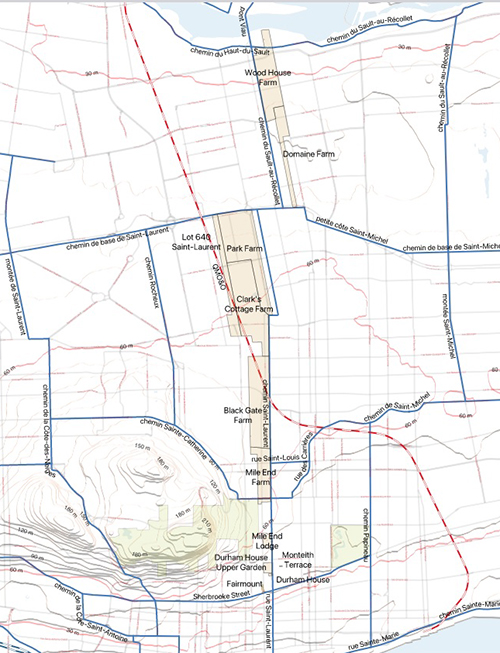

This view of the city of Montreal from the slope of Mount Royal was painted by artist James Duncan in 1832. In the distance, the city was on the banks of St. Lawrence River, while in the foreground, the foot of the mountain was rural and traversed by only one road – today’s Saint-Laurent Boulevard.

Today, this area is a dense neighbourhood of homes, shops and commercial buildings, but 200 years ago, it was described as a neighbourhood of rural villas. Several of those homes belonged to my ancestors, including butcher John Clark (1767-1827) and merchant Stanley Bagg (1788-1853). These buildings were all torn down years ago, but fortunately, artists and photographers captured them before they disappeared. This article tells their stories.

Saint-Laurent Boulevard began as a country road passing through a landscape with a mix of rural functions. In the 1700s, a large tannery was located nearby, to the east along Mount Royal Avenue. Later, numerous quarries were excavated to provide the grey limestone used for much of Montreal’s Victorian architecture – churches, civic buildings, places of business and attractive houses. The Beaubien family acquired a large tract of land along the east side of the road in 1842, as well as property in what later became the municipality of Outremont. A railway line was built across the Bagg and Beaubien land in 1876, along which an industrial corridor emerged in the early 1900s.

During the lifetimes of the Clarks and Baggs, their property, on the west side of Saint-Laurent, was farmland. The soil was mostly sandy and rocky. Hay to feed cattle and horses was the main crop, but vegetables and fruit trees could be grown in fertile areas. Back from the road, rising up toward the side of the mountain, there were a handful of rural villas belonging to the Baggs and a few neighbours, including the Perrault-Nowlan and the Hall families.

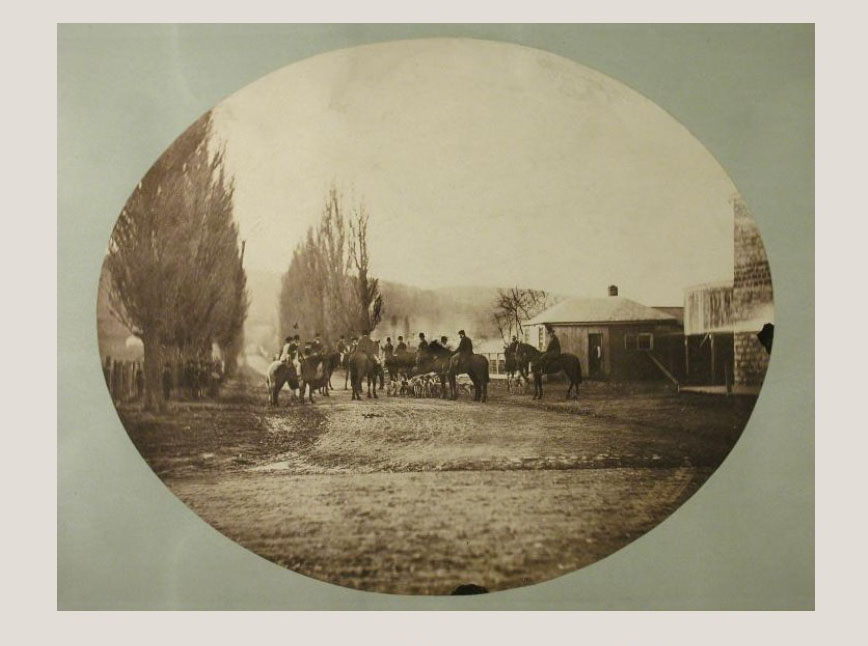

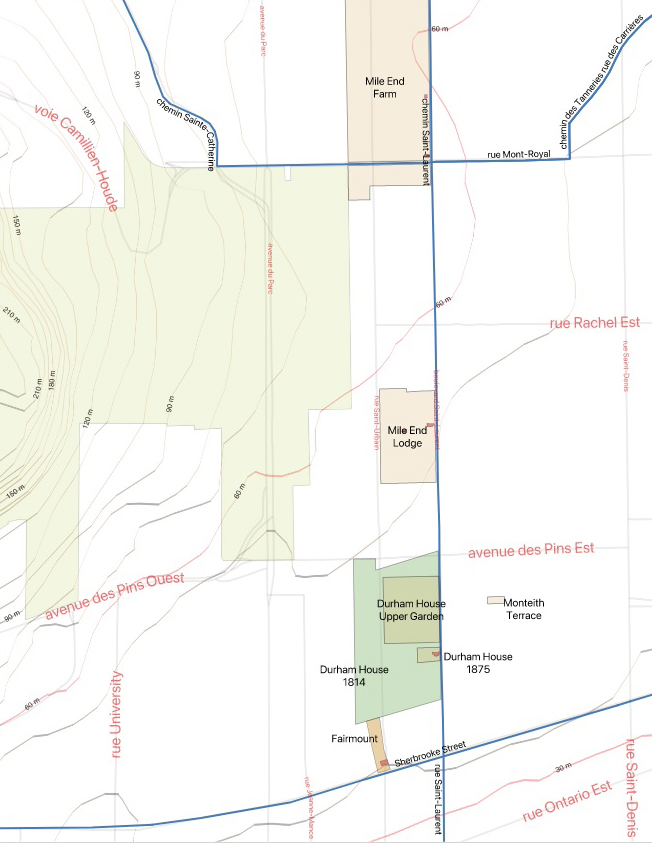

Butcher John Clark, my four-times great-grandfather, was the first member of my family to live in this area. He brought his wife and young daughter to Montreal around 1797 from County Durham, in northern England, and began investing in land. In 1804, Clark purchased a farm on the west side of Saint-Laurent, and over the next few years, he added adjacent parcels of land. He called the property Mile End Farm, probably inspired by Mile End in London, England.1 His choice of name is still familiar today, as this neighbourhood is known as Mile End. In 1810, he leased the farm to American-born Phineas Bagg (c. 1751-1823) and his son Stanley,2 and they ran an establishment called the Mile End Tavern there until 1818.

After Phineas retired and Stanley moved on to other business interests, various tenants operated the Mile End Tavern. It was demolished in 1902 when the local municipality expropriated the land to widen Saint-Laurent Boulevard. New owners purchased the lot in 1905, and the following year a department store opened on the corner of Saint-Laurent and Mount Royal Avenue, where the tavern had stood for so long.3 The department store was converted into a commercial building during the Great Depression. Today, a Couche Tard convenience store and a Tim Horton’s coffee shop are on its ground floor.

By 1891, both Stanley Bagg and his son Stanley Clark Bagg had died and most of the Mile End Farm property was sold by the late Stanley Clark Bagg’s five adult children to developers McCuaig and Mainwaring.4 An economic depression and lack of basic services such as sewers and tramways delayed development for a few years. Meanwhile, the most valuable lots – the ones that faced Saint-Laurent Boulevard – were divided into five equal shares and allocated at random to the five Bagg siblings.5

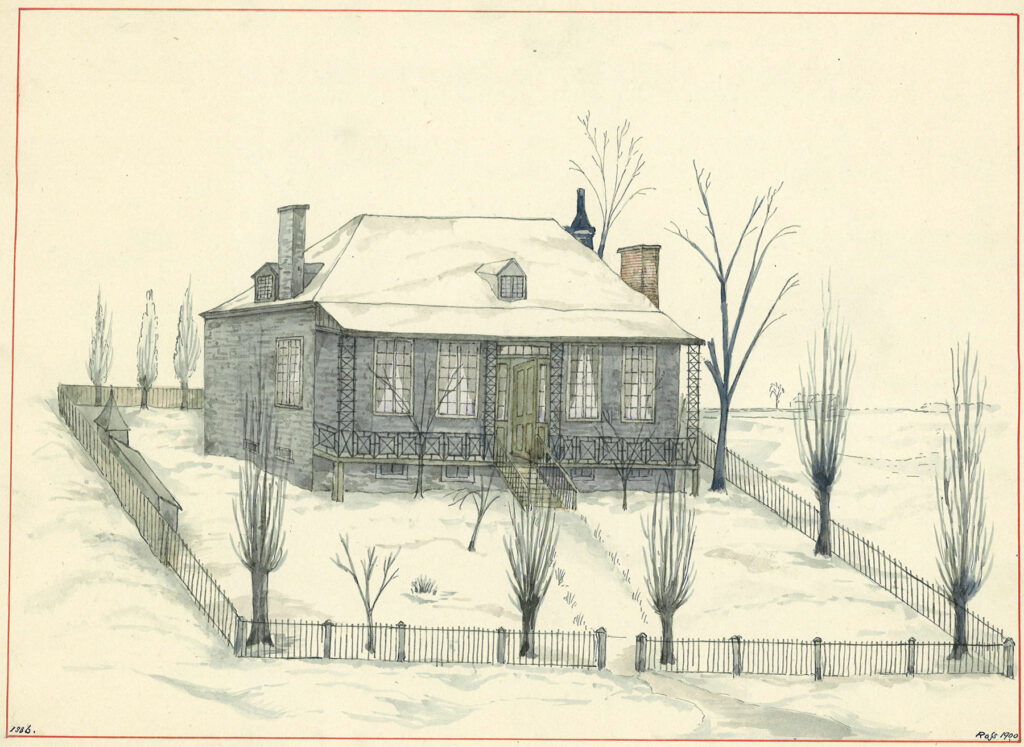

John Clark’s house was not as well known as the nearby tavern. In 1815, Clark sublet a 16-acre square of land back from the Baggs, a “piece of ground on which is erected a new house of butchery called by the said John Clark, Mile End Lodge”6 – in reality, a two-storey stone house for his family. Facing south, toward the city and the river, it was located between the current Bagg and Duluth Streets, just above what was then the Montreal city limit. Clark also sublet a strip of land in the axis of Park Avenue for unspecified purposes.

After Clark’s death in 1827, his widow, Mary Mitcheson Clark, moved to a smaller house at the current northwest corner of Bagg and Clark Streets. An inscription noting that this was once the location of the Mitcheson Cottage can still be seen on the foundation of the house that stands there today.

As for Mile End Lodge, although it remained in the hands of Clark’s descendants, no family members ever lived there again. Various tenants rented it over the years. The land around it was subdivided, with a chunk sold in 1873 and the rest in 1893, but the house itself was not sold until 1914. The badly deteriorated building was demolished soon after that, and there is now a large commercial building in that location.7

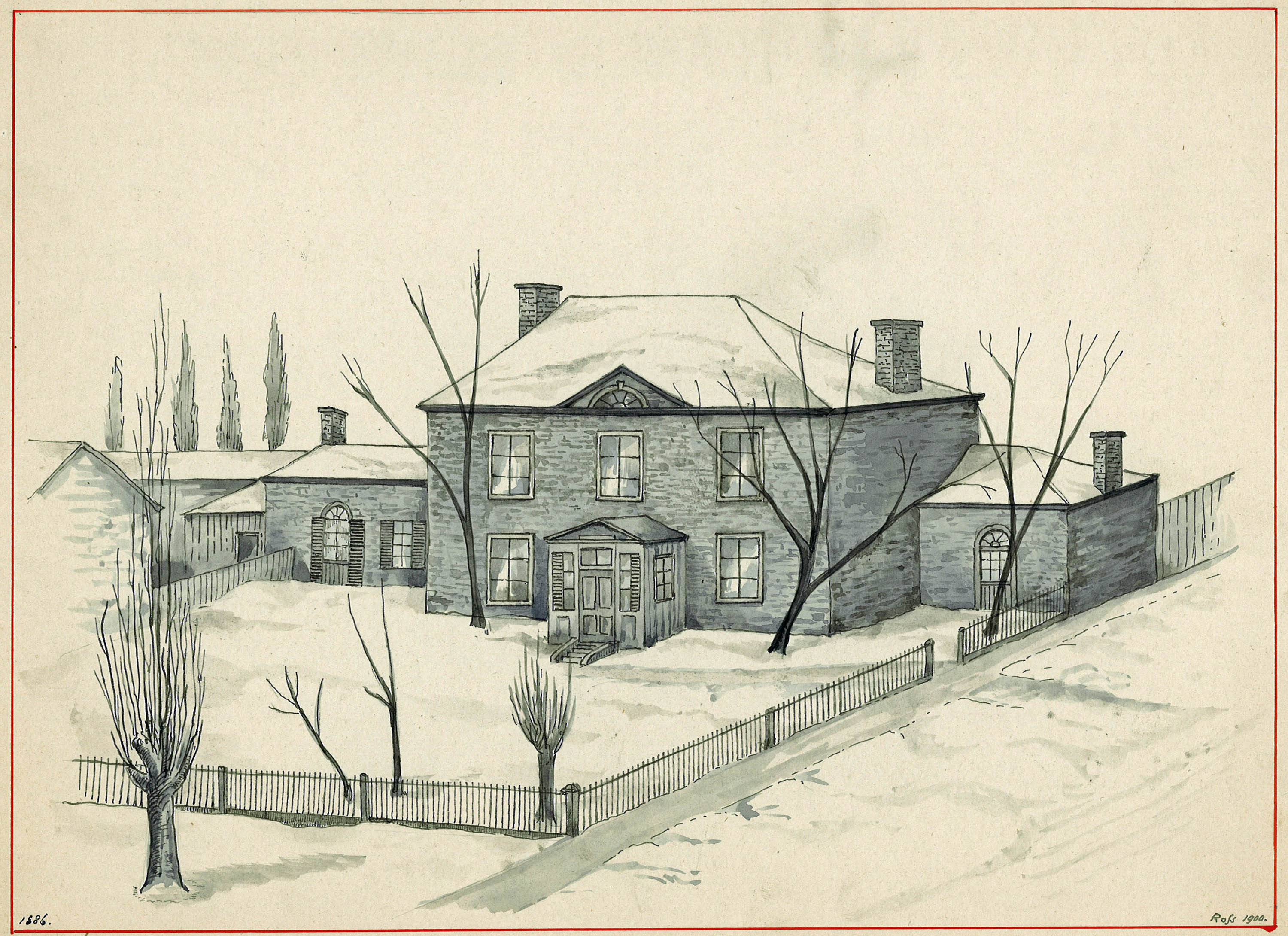

Durham House, the home of my three-times great-grandparents Stanley Bagg and Mary Ann Clark, was located south of the tavern and Mile End Lodge. John Clark purchased the property in December, 1814 and gave it to his daughter as a wedding present in 1819. Durham House was on Saint-Laurent Boulevard, at the current southwest corner of Prince Arthur. Early references describe its address as Côte à Baron.

This two-storey stone building, also faced south. There was a covered well on the property, a barn and several other outbuildings. The original Durham House property measured 6 ¾ x 4 arpents, so it was a sizeable piece of land, including property between Prince Arthur and Guilbault Streets, known as the Upper Garden.

After Stanley Bagg’s death in 1853, Durham House was briefly used as a school, then it housed a fruit store for a number of years. Meanwhile, the large property that surrounded it was one of the first to be subdivided for building lots. Stanley Clark Bagg subdivided it in 1846, and the Upper Garden was subdivided by his heirs in 1889. The house was demolished in 1928 to allow for the expansion of the modern TD Bank branch which sits on the spot today.

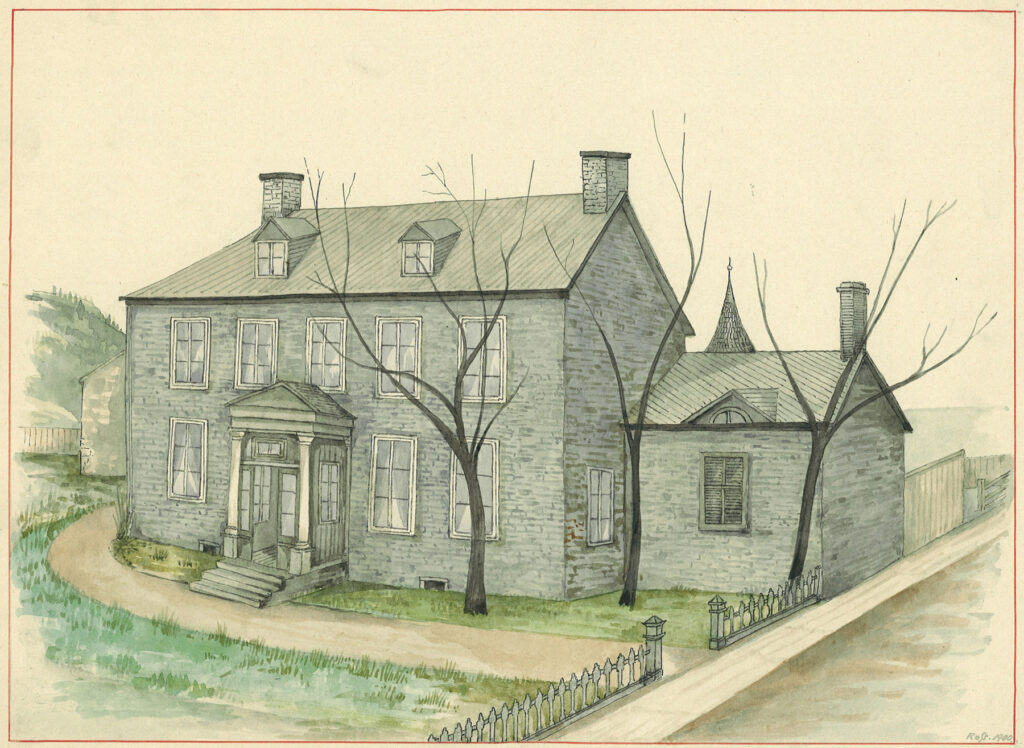

Stanley Bagg purchased land near the corner of Sherbrooke Street and St. Urbain at a sheriff’s sale in 1837, and sold it to his son in 1844. Stanley Clark Bagg and his wife, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg (1822–1914), built a large house they called Fairmount Villa on that lot and raised their five children there. The house included a small chapel, while the irregularly shaped property, which extended to the boundary of the Durham House land, had a garden with lilac trees, statues and flower beds. The house was likely named after Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, where Catharine grew up.

Stanley Clark Bagg died in 1873, but Catharine remained at Fairmount Villa for the rest of her life. The house was sold in 1915, and it was demolished in 1949 when Saint-Urbain Street was widened.

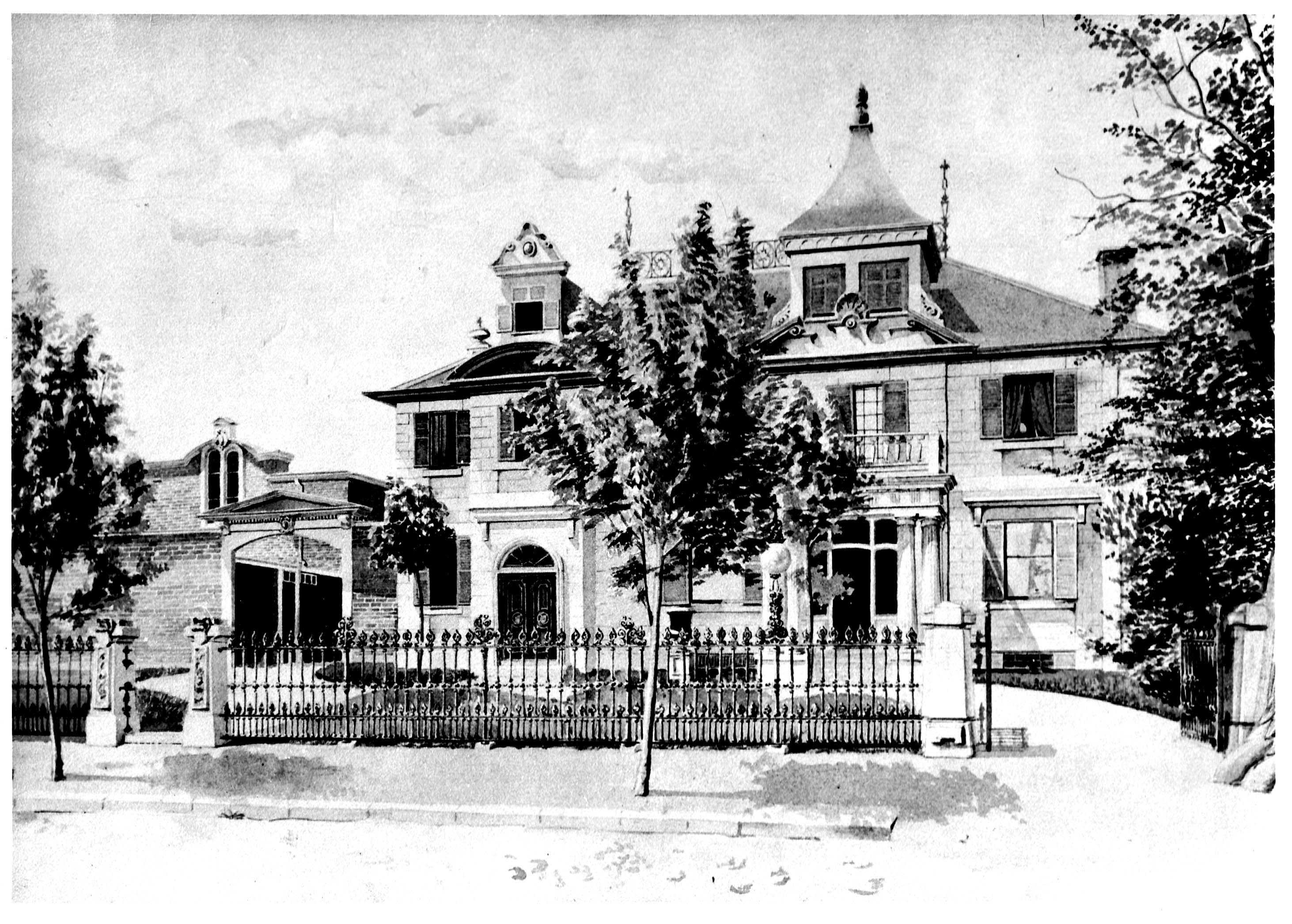

The Fairmount property (lot 100 of the cadastre of St. Lawrence Ward) was subdivided in 1872, then redivided in 1922. In 1884, Stanley Clark Bagg’s son, Robert Stanley Bagg (1848-1912), built a house on one of the subdivided lots, at 436 (later 3470) Saint-Urbain. He and his young family moved to a bigger house in a more exclusive neighbourhood on Sherbrooke Street West a few years later, and his sister Mary Heloise Lindsay and her family lived in the house on Saint-Urbain from 1890 until 1906. The house changed street numbers several times, then changed vocations: it became part of the Herzl Jewish Hospital, was subdivided into apartments, and was finally demolished in the early 1960s.

Today, two large buildings that once housed Montreal’s school of fine arts are located on the former Fairmount property. The smaller one, of yellow brick, at 3450 Saint-Urbain, was designed by celebrated architects Omer Marchand and Ernest Cormier in 1923 for the École des beaux arts de Montréal. It will soon be home to Montreal’s new Afro-Canadian Cultural Centre. The larger building, at 125 Sherbrooke St. W., a heritage building constructed in 1905 as the Commercial and Technical High School, later became the Marie-Claire Daveluy building of the Bibliothèque nationale du Québec (1982–1997). It has housed l’Office québécoise de la langue française since 1999.

Notes:

Built by the Sulpician priests in 1717, Saint-Laurent Boulevard was initially known as a grand chemin du Roy – Great King’s Highway. Over the years it has been known by many names, both English and French, including Chemin Saint-Laurent, St. Lawrence Street and “the Main”. Since 1905, it has been designated Boulevard Saint-Laurent.

The name Côte à Baron, or Coteau Baron, cannot be found on today’s city maps, but in the late 19th century, this was the name of a sloping stretch of Saint-Laurent Boulevard just below Sherbrooke Street and extending a short distance north of there. Côte à Baron was described as a neighbourhood of rural villas. The first-ever Lovell’s city directory for Montreal, published in 1842, listed Stanley Bagg’s home at Côte à Barron. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3652365). Another building with a Côte à Baron address, at the northwest corner of Sherbrooke Street and Saint-Laurent, was an extravagant mansion nicknamed Torrance’s Folly. It was built around 1815 by businessman Thomas Torrance and sold to John Molson in 1832. A gas station is now located at that corner.

An arpent is a French unit of measurement that can refer to either area or length. It is equivalent to an acre of land, or about 58 metres in length. It has been replaced by metric measures since 1970, but can still be found in old property records.

Source of the photo of the Herzl Dispensary: The Jew in Canada: a complete record of Canadian Jewry from the days of the French régime to the present time, ed. Arthur Daniel Hart, 1926 (on BAnQ numérique).

This story is also posted on the collaborative family history blog Genealogy Ensemble. It was updated on Sept 17, 2025 to add the photo of the Herzl Dispensary.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “The Mile End Tavern”, Writing Up the Ancestors, October 21, 2013 https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/the-mile-end-tavern.html

Janice Hamilton, “John Clark, 19th Century Real Estate Visionary”, Genealogy Ensemble, May 22, 2019, https://genealogyensemble.com/2019/05/22/john-clark-19th-century-real-estate-visionary/

Janice Hamilton, “The Life and Times of Stanley Bagg, 1788-1853”, Writing Up the Ancestors, October 5, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/10/the-life-and-times-of-stanley-bagg-1788.html

Janice Hamilton, “A Home Well Lived In”, Writing Up the Ancestors, January 21, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/01/a-home-well-lived-in.html

Janice Hamilton, “Fairmount Villa”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Dec. 18, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/12/fairmount-villa.html

Janice Hamilton, “Bagg Family Dispute Part 2: Stanley Clark Bagg’s Estate”, Genealogy Ensemble, Feb. 14, 2024, https://genealogyensemble.com/2024/02/14/the-bagg-family-dispute-part-2/

Janice Hamilton, “History of a Downtown Montreal Property”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Dec. 31, 2022, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2022/12/history-of-a-downtown-montreal-property.html

Justin Bur, “À la recherche du cheval perdu de Stanley Bagg, et des origines du Mile End.” A la recherche du savoir: nouveaux échanges sur les collections du Musée McCord; Collecting Knowledge: New Dialogues on McCord Museum Collections. Joanne Burgess, Cynthia Cooper, Celine Widmer, Natasha Zwarich. Montreal: Éditions MultiMondes, 2015.

Mile End Memories, http://memoire.mile-end.qc.ca/en/

Sources:

1. Justin Bur, Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée, Joshua Wolfe, Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), p 256.

2. J.A. Gray, n.p. no 2874, 1810-10-17

3. Justin Bur, Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée, Joshua Wolfe, Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), p 258.

4. William de Montmollin Marler n.p. no 17571, 1891-11-20

5. John Fair n.p. no 3434, 1892-05-18

6. Henry Griffin, n.p. no 931, 1815-04-15

7. Justin Bur, Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée, Joshua Wolfe, Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), p 259.