Dr. Thomas Glendenning Hamilton (1873-1935) became internationally famous because of his investigations into psychic phenomena.1 But his more mundane activities probably had a greater impact on the lives of his patients, friends and colleagues than his psychic research did.

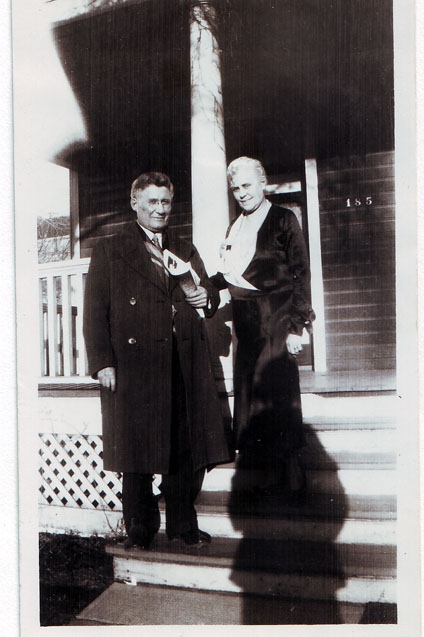

TGH, or T. Glen Hamilton,2 as he was known, grew up in a farming family, first in Ontario and then in Saskatchewan. He graduated from Manitoba Medical College in 1903, at age 30. After interning for a year, he set up a practice in medicine, surgery and obstetrics in Elmwood, a suburb of Winnipeg. Several years later, he and his wife, Lillian, moved into a large house in the neighbourhood. They raised their family there, and he had an office on the ground floor.

Elmwood’s first doctor, he was the kind of old-fashioned physician who made house calls (by horse and buggy in the early years) and delivered babies at home.3 According to his daughter, Margaret, his outstanding quality was his genuine concern for people: “To his many patients, he was not only the beloved physician, but he was the staunch friend and wise counsellor as well.”4

He plunged into community involvement and was elected to the Winnipeg Public School Board in 1907. Perhaps his experience as a teacher before he went to medical school inspired his interest in education. He remained on the school board for nine years, serving as chairman in 1912-13 and helping to guide the board as it built several new schools in the fast-growing city. He helped to establish fire drills and implement free medical examinations for public school students, and he believed in the benefits of playground activities.

He was a member of Elmwood Presbyterian Church (later known as King Memorial United Church) from the time he settled in Elmwood. An elder for 28 years, he was chairman of the building committee and helped raise funds for the construction of the church.5

In 1915, TGH resigned from the school board after he was elected to the Manitoba Legislature as the Liberal member for Elmwood. At that time, his riding stretched all the way to the Ontario border. These were times of social change. Manitoba’s Liberals brought in several landmark bills, including the right to vote for women, the mother’s allowance act and workmen’s compensation. Nevertheless, a strong Labour vote swept the Liberals from power in the 1920 provincial election and TGH lost his seat.

He then shifted his energies to the medical field. He was a lecturer in the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Medicine, and a member of the surgical staff of the Winnipeg General Hospital. He wrote several articles that were published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal on the treatment of hand injuries, on the incidence of goiter (enlarged thyroid) in children, and on ulcerative colitis. He served as president of the Manitoba Medical Association in 1921-1922, and he was a member of the executive committee of the Canadian Medical Association from 1922 to 1931. He founded the Manitoba Medical Review and he was the first president of the alumni association of the University of Manitoba.6

All these volunteer activities in addition to his medical practice must have made him a very busy man. Nevertheless, after the death of his three-year old son Arthur from influenza in 1919, he found time for a new passion: psychic phenomena. His ultimate question was whether some part of the human mind, consciousness, or personality survives bodily death.

For more than a decade, he and Lillian organized weekly séances at their home, watching tables that moved on their own and communicating with spirits. He tried to take a scientific approach to his observations and to prevent fraud, so he took hundreds of photos of these events.

When TGH addressed an audience of Winnipeg physicians about his research in 1926, he was afraid he would lose his professional reputation as a result, but they listened to him with what he later acknowledged was “a tolerant and good-natured skepticism.”7 Most of them probably did not agree with his comments, but he had accumulated a bank of good will through his many professional and volunteer activities, and he had a strong reputation for integrity.8

When he died of heart attack in 1935, at age 61, hundreds of people filled King Memorial United Church, where he had been active for so long, to say goodbye to this man who had been such an important part of the community.9

This article is also posted on https://genealogyensemble.com

See also:

“Tales of a Prairie Pioneer” Writing Up the Ancestors, Feb. 1, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/02/tales-of-prairie-pioneer.html

“Five Brothers,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Dec. 1, 2018, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2018/12/five-brothers.html

“The Legacy,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 4, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/01/the-legacy.html

“Arthur’s Baby Book,” Writing Up the Ancestors, March 29, 2017, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2017/03/arthurs-baby-book.html

Sources and Notes:

- The Hamilton Fonds at the University of Manitoba Archives includes photos, letters, lecture notes, newspaper clippings and other documents related to TGH’s life and research interests. See “Hamilton Fonds” University of Manitoba Libraries, http://umanitoba.ca/libraries/units/archives/digital/hamilton/index.html

- Although TG was my paternal grandfather, I never met him. He died many years before I was born.

- “Elmwood’s First Doctor,” TheElmwood Herald, June 10, 1954.

- Margaret Hamilton Bach. “Life and Interests of Dr. T. Glendenning Hamilton.” Proceedings of the First Annual Archives Symposium. University of Manitoba Department of Archives and Special Collections, 1979, p 89-90.

- For more information about the church, see “Historic Sites of Manitoba: Elmwood Presbyterian Church / King Memorial Presbyterian Church / King Memorial United Church / Gordon-King Memorial United Church,” Manitoba Historical Society, http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/gordonkingmemorialunited.shtml, accessed Feb. 22, 2019.

- Ross Mitchell, M.D. “Dr. T. Glen Hamilton, the Founder of the Manitoba Medical Review,” The Manitoba Medical Review, vol. 40, no. 3, p 219.

- Margaret Hamilton Bach, Ibid, p. 92.

- Dr. Charles G. Roland, “Glenn – the Mystical Medic from Manitoba,” Ontario Medicine, May 18, 1987, p. 29.

- “Death of Dr. T. Glen Hamilton Ends Life of Marked Achievements,” The Elmwood Herald, April 11, 1935.