When my son Michael and his long-time girlfriend Jennifer get married this weekend, it will be a very traditional ceremony. The wedding will take place at Montreal West United Church, the same church where Jen’s parents were married. Jen will wear a long white dress, a borrowed pair of earrings and blue shoes.

Here’s their story as they tell it: “This wedding is a love story 13 years in the making! We first met in CEGEP [junior college] when we were just teenagers. At the groom’s insistence, mutual friends organized our first meeting: a competitive game of pool at Sharx on St. Catherine Street. A new friendship was born and, after 10 years of ups and downs, we somehow managed to remain a part of each others’ lives. And it was all meant to be because this October, after almost four years of dating, we’ll be making it legal. It’s till death do us part now, and we couldn’t be happier!”

All this has led me to think about some of the other weddings in my family, and about how much courtship has changed. A huge change came in my parents’ generation. Prior to World War II, many Canadians married within their own social circles. Couples often grew up in the same small towns or went to school together. But during the war, as men joined the military and women joined the workforce, people met new friends and were exposed to different ideas. My father was from Winnipeg and my mother grew up in Montreal, but they met in Ottawa during the war and were married in 1946.

My father’s parents, Thomas Glendenning Hamilton and Lillian Forrester, probably met at the Winnipeg hospital where he was a doctor and she a nurse. They were married in 1906 at Lillian’s uncle’s home. Going back another generation, James Hamilton and Isabella Glendenning, who married in 1859, both grew up in a close-knit farming community in what is now Scarborough, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto. They may have met at the church both their families attended, St. Andrews Presbyterian Church.

On my mother’s father’s side, when Jane Mulholland, the daughter of a Montreal hardware merchant, met John Murray Smith, she was smitten. John, however, lived in Ontario at the time, where he worked at a bank. According to a family story, she told her nanny that she admired this young man and the nanny wrote a letter that brought couple together. It would have been difficult for Jane to pursue John long-distance on her own behalf. They married near Montreal in 1871.

Going back another generation on the Smith side, James Avon Smith was an assistant school teacher in MacDuff, Scotland. When he married the schoolmaster’s daughter, Jean Tocher, in 1823, she was already pregnant.

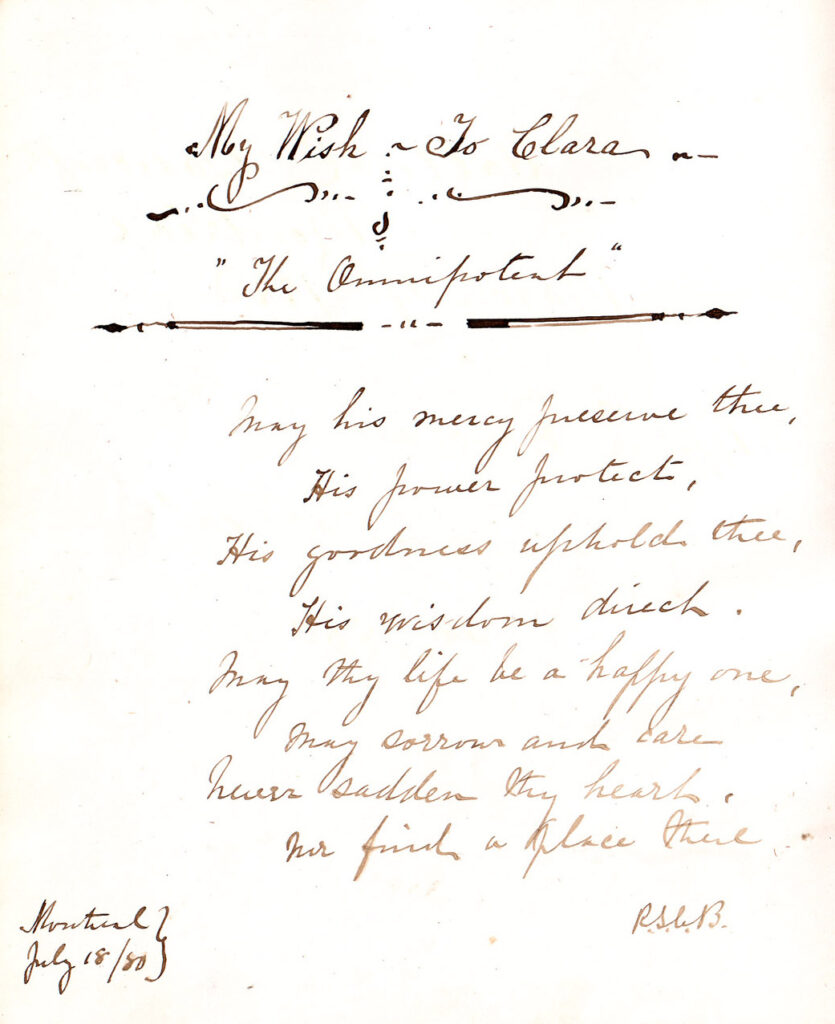

Most parents tried their best to prevent this situation. It was not considered proper for young couples to spend time alone together and when my future great-grandparents Robert Stanley Bagg and Clara Smithers began courting in 1880, they would have always been surrounded by friends and family members. He wooed her by writing poems in her autograph book.

The 1844 wedding of Robert Stanley’s Bagg’s parents was a genealogically significant event on my mother’s side of the family because Stanley Clark Bagg and Catharine Mitcheson were first cousins once removed. Marriage between cousins was not uncommon, but I can’t help wondering how they met, since she lived in Philadelphia and he lived in Montreal. They were married in Philadelphia, with Catharine’s brother Rev. Robert McGregor Mitcheson officiating.

The fact that Mike and Jen are getting married, as opposed to living common-law as many couples do in Quebec today, is a mark of their commitment to each other as much as it is a nod to tradition. I am very happy for them.

Further Reading

For more on the courtship and marriage customs of our Canadian ancestors see this article prepared by Library and Archives Canada: “I Do: Love and Marriage in 19thCentury Canada”, http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/love-and-marriage/index-e.html

Marriages between cousins contribute to a phenomenon called pedigree collapse in which the family trees of these peoples’ descendants are smaller than they would be otherwise. There are many articles about this phenomenon online, including this one by the International Society of Genetic Genealogy, http://www.isogg.org/wiki/Pedigree_collapse