There are lots of stories about my three-times great-grandparents John and Marjory MacFarlane. He was born in 1791, she was born in 1801. He was a stonemason who left Scotland after a fight with his brother and business partner, Donald. He invested in an oatmeal mill in Upper Canada and lost everything when it burned down. They had nine children, two of whom died as children.

Unfortunately, I cannot yet document any of these stories. There are a few facts, however, that can be confirmed.

The marriage of John MacFarlane and May Robertson on 26 December, 1823 was recorded in the records of Clunie parish, Perthshire. Their first child, Janet (my great-great-grandmother,) was baptized in Clunie parish on 26 June, 1825.

The family arrived in Upper Canada around 1833. They settled in Melrose, Tyendinaga Township, Hastings County, near today’s Belleville, Ontario, where they were included in the 1861 census of Canada. One of John and Marjory MacFarlane’s descendants is still raising cattle across the road from the original family farm.

I been unable to confirm John MacFarlane’s date or place of birth although, according to a copy of a family letter, author unknown, he was born 4 March, 1791.

John’s wife is referred to in various documents as Marjory, May and Margaret. There is a baptismal record for a Marjory Robertson, dated 15 March, 1801 in Caputh parish, however, her gravestone in Ontario gives her dates as 1804-1870. Was that the baptismal record of another child, or is there an error in the monumental inscription?

It does seem probable that the family lived in or near tiny Clunie parish. Family stories say they came from near Dunkeld and the Tay River. Both Clunie and Caputh parishes are very close to Dunkeld, a cathedral town with an old bridge over the Tay.

Gravestones, marriage and census records confirm most of their children’s names and some dates: Janet (1825-1901) married James Drummond Forrester; Christina, born 1827, was included in the 1861 census and then disappeared; John (1828-1907) married Letitia McKinney; Margery (1831-1835) died as a child, according to a family letter; Jean (1833-1883) married Ed Carscallen, and her marriage and death records confirm family stories that she was born on the Atlantic; Donald was born 1835, according to family records, and probably died as an infant; William (1838-1917) married Mary Jane McKinney; Margery, or Marsley (1840-1886) married James Balcanqual; Donald (1843-1900) married first, Helen Pegan, and second, Mary Anderson.

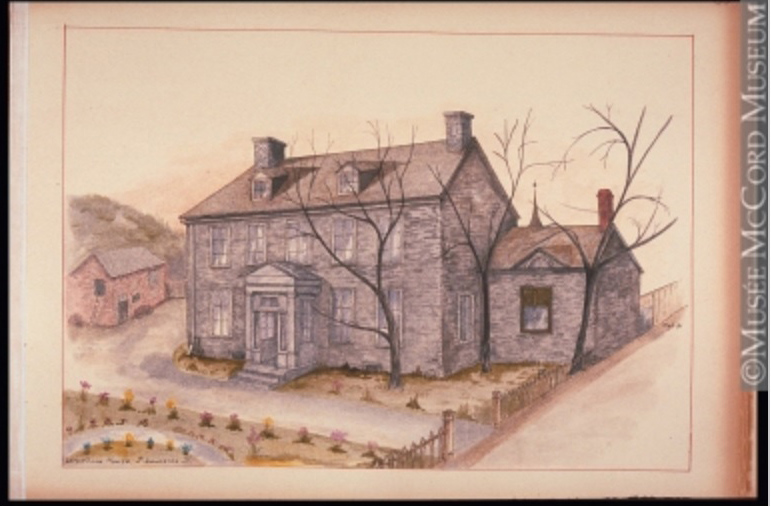

I am curious to know whether John MacFarlane was a stonemason before he came to Canada as one family story suggested. Maps and gazetteers dating from the 1800s indicate there were quarries in the Clunie region, so it is a possibility.

Did John build a mill in Melrose? Again, it is possible. In his book Historic Hastings, Gerald Boyce says, “The centre’s first grist mill had been built in 1833 by Mr. McFarlane …” More research is needed to clarify whether this was my John MacFarlane or someone else.

Research notes: Two topics worth discussion arise from this article. The first is Genealogical Proof Standard, or GPS. (See https://familysearch.org/learningcenter/lesson/genealogical-proof-standard/350.) The five central points of GPS are: the genealogist must do a reasonably exhaustive search; cite sources fully; analyze the collected information; resolve any conflicting evidence; write a coherent conclusion.

There are several conflicting pieces of information about this family, and I need to gather additional, reliable evidence to sort out fact from fiction. Maybe I’ll find all that evidence some day but, in the meantime, I do know enough to begin to tell their story.

There is an inconsistency in the spelling of the family’s name. The gravestones in Gilead St. Andrew’s Cemetery and Melrose Cemetery, where most of these people are buried, spell it Mac, while family members now insist it is Mc; just another genealogical challenge, but no big deal.

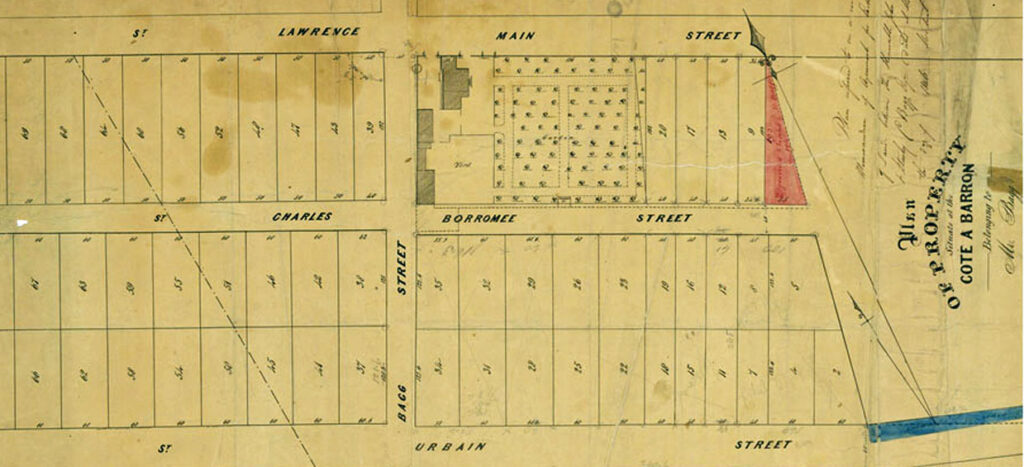

The second topic involves one of my favorite genealogy research tools: maps. As well as being beautiful, old maps often show the locations of roads and structures that existed in our ancestors’ times, but are no longer visible. The National Library of Scotland has an extensive collection of digitized maps at www.nls.uk/collections/maps. I also found a good map showing Clunie Parish Church and its surroundings on the excellent Scotland’s Places website, http://www.scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/.

A solidly researched history of Hastings County, first published in 1967, has recently been updated and can be ordered from www.globalgenealogy.com. Historic Hastings,Volume One, with New Introduction and Expanded Index, by GeraldE. Boyce, is published by Global Heritage Press, Milton, 2013.