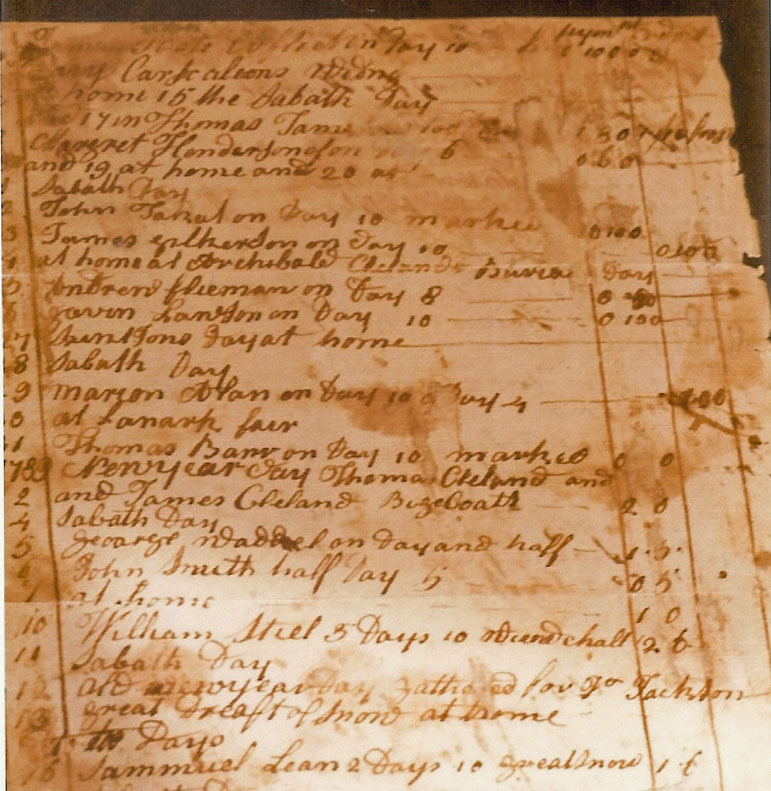

As a tailor, Robert Hamilton was often on the road, visiting customers’ homes to fit and sew their clothes on the spot. But the winter of 1789 was a cold one in Lesmahagow, Scotland and, on January 12, there was a “great draeft of snow” that kept him at home. Robert recorded these work trips, as well as special events such as the Lanark Fair and a friend’s burial day, in a ledger. Two pages of that ledger were slipped into the family Bible, which his son brought to Canada.

Robert Hamilton, my three-times great-grandfather, was born around 1754. He married Janet Renwick in 1783 at Lesmahagow parish church. The church record said both were of Abbey Green, the old name for Lesmahagow.

Robert and Janet had five children: Margaret, born 1784; Robert, 1789; Agnes, 1791; Archibald, 1794; and Janet, 1800. Archibald died as an infant, and I do not know what happened to Margaret. Around 1830, Agnes, Robert jr., and Janet all settled in Scarborough, which is today a suburb of Toronto, Ontario.

When Robert and Janet were bringing up their young family, Lesmahagow parish was a good place to live. Just south of Glasgow, it was, and still is, beautiful, with rolling hills, streams and ravines. The Statistical Accounts of Scotland 1791-1799 noted, however, that the soil was not particularly fertile, more suited to pasture for sheep and cows than to growing crops. Everyone grew potatoes and, in his ledger, Robert reported spending several days in mid-October “raising potatoes.”

The Statistical Accounts described the people as mostly “healthy and robust,” their moral deportment “decent and regular.” The children learned English, Latin, geometry and arithmetic at the local schools. Robert’s ability to read and write was not unusual.

In 1799, the majority of the parish’s 3,000 residents were husbandmen (farmers), and there was a small coal mining industry. There were also numerous tradesmen, including blacksmiths and carpenters, and some 26 tailors and 62 weavers. In the first decade of the 19th century, skilled cottage weavers made wool and linen cloth in their Lanarkshire homes. Then a recession hit and Glasgow factories undermined the cottage weaving industry. Even the climate deteriorated, affecting crops. By 1819, thousands of people in Lanarkshire were living in poverty. Some joined organizations such as the Lesmahagow Emigration Society, and the government assisted them to move abroad.

Janet died in 1821 and Robert survived another ten years, long enough to watch his children leave for Canada. The Hamiltons were buried in the old Lesmahagow parish cemetery. When I visited it in 2012, I searched in vain for their gravestone. All I could find was an empty space in the spot where a diagram suggested it had once stood.

Research Remarks: I am as fascinated by local and social history as I am by genealogy. Even if I don’t know the details of my ancestors’ experiences, I like to find out about the specific times and places in which they lived. The Statistical Accounts of Scotland provide contemporary descriptions of life in Scotland, based on information supplied by local church ministers. Two series were published, one at the end of the 18thcentury, another in the 1830s. You can browse The Statistical Accounts of Scotland, Account of 1791-99 vol. 7, p. 420: Lesmahago, County of Lanark online for free, http://edina.ac.uk/stat-acc-scot/

Another source of social history is A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600 to 1800, edited by Elizabeth Foyster and Christopher A. Whatley, Edinburgh University Press, 2010. It mentions the high esteem in which skilled craftsmen such as tailors and weavers were held, although this changed over time. By 1800, many people were buying ready-made clothes in shops.

Scottish gravestones can also be quite revealing. Although the Hamiltons’ stone seems to have disappeared, the inscription was recorded in Monumental Inscriptions (pre-1855) in the Upper ward of Lanarkshire, by Sheila A. Scott, published by the Scottish Genealogy Society, 1977. It read, “Robert Hamilton tailor Abbey Green, 18.11.1831, 77. w. Janet Renwick, 9.5.1821, 63. s. Archd. Inf.”

see also: Janice Hamilton, “From Lesmahagow to Scarborough,” Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/12/from-lesmahagow-to-scarborough.html