Big cities usually act as magnets, attracting people from the countryside to the excitement and employment opportunites urban centres offer. But several adult children of Henry and Sophia Smithers did the opposite: born in greater London at the beginning of the 19th century, they scattered across Engand and beyond as adults.

Henry Smithers (1762-1828) was born in London, while his wife, Sophia Papps (1763-1845) was born in Salisbury, Wiltshire, not far from Stonehenge. They were married in 1783 at St. Matthew’s Parish Church, Bethnal Green, and had seven children.

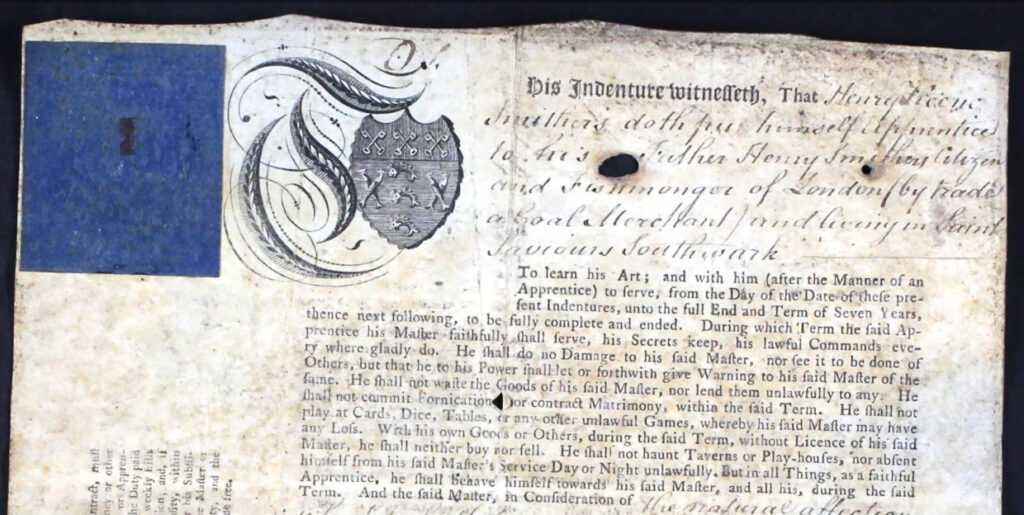

Henry Keene Smithers was born in St. Andrews Holborn parish, London in 1785. His birth and that of his sister Charlotte Sophia were registered simultaneously in the non-conformist records on Dec 14, 1789. After being apprenticed to his father, he became a coal merchant, then a general merchant and accountant. He and his wife, Charlotte Letitia Pittman, and their eight children lived in Southwark, on the south bank of the Thames River. He died in 1859. He was my three-times great-grandfather, and I have written in greater detail about his life and beliefs in two previous posts.

Charlotte Sophia Smithers was born in St Saviour’s Parish, County Surrey, in April 1789, so the family must have moved across the Thames before she was born. I know very little about her life except that she did not marry and was living with her brother Henry Keene Smithers and his wife in St. Giles, Camberwell at the time of the 1841 Census of England.

By the time the 1851 census took place, she was age 61 and living as a lodger with a Baptist minister’s family in Bedfordshire. She described herself as an annuitant, meaning she had some private income. She died a few months later.

Martha Keene Smithers, born in 1790, was said to have been a great beauty. She married John Van Cooten, at St. Woolos Church in Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales in 1808. (Newport was an important coal-exporting port at the time, and her father had a business there; it went bankrupt in 1812.) Martha and John had six children, at least one of whom was born in the Netherlands. (John’s father was originally from the Netherlands, but he became a sugar plantation owner in Demerara, Guyana, South America, which is where John was born.)

Their marriage must have been an unhappy one because, according the Van Cooten family website, Martha went to the West Indies, leaving John and their young children behind. She eventually returned to England, but, although she and John did not divorce, they never lived together again. Her brother Sydney, who was steward to the Duke of Devonshire, supported her. At the time of the 1851 census she was living with her daughter Anna in London. She was buried in the parish of St. George Bloomsbury, London in 1854.

John Hampden Smithers was born in Southwark, Surrey in 1792, and his birth, like that of his older siblings, was registered at the Maze Pond Baptist Church. He was likely named after English politician John Hampden, who challenged the authority of King Charles I and was killed in battle in 1643 at the outset of the Civil War in England.

In 1806, when brother Henry Keene was wrapping up his apprenticeship, John became apprenticed to his father. John was admitted to the Freedom of the City of London by patrimony in 1815. Also in that year, the business he and his father owned on Oxford Street in London went bankrupt.

In 1822 John married Amsterdam-born Elizabeth Hoffmann by license at St. Marylebone Church, London. They had five children, the eldest daughter baptized in London, a son baptized in Liverpool, and the two youngest daughters, born 1827 and 1830, baptized in Derbyshire. All the children were baptized in the Anglican church. In 1827 John, a provision merchant in Liverpool, went bankrupt a second time. Soon after that the family appears to have moved to the city of Derby.

The 1851 census showed John, his wife and three daughters living in London. John gave his occupation as proprietor of houses (basically a landlord.) I did not find the family in 1841 or 1861 in the British Isles, so perhaps they were living in Europe. He died in 1867 in Nice, France and was buried in the Anglican cemetery there.

Sydney Smithers was born in Southwark around 1795. I have not found any record of his birth or baptism. He married Catherine Longsdon in 1822 in Youlgreave, Derbyshire, and they had three children baptized in the Church of England. Sydney worked for William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire. A Whig in politics (he supported liberalizing restrictions on Catholics and abolishing slavery,) the duke was friends with kings, writers and botanists. He owned several vast estates, including one in Derbyshire. Sydney and his family lived in Ashford, Derbyshire, and his duties probably involved managing the duke’s household and estate there. Sydney died in 1856, age 61.

Augusta Sophia Smithers, was born in 1799 or 1800, and was baptized in 1827. Adult baptism is normal for a member of the Baptist church, but several things suggest this baptism was not a happy occasion.

The baptism took place on August 26, 1827 at the Anglican Church of St. Mary Edge Hill, near Liverpool, where her brother John lived. Her parents were Baptists, but it appears that Augusta Sophia was converting to the Anglican religion. The register of the baptism listed her father’s name, but her mother’s was left blank. Perhaps her mother did not attend the service that day.

Like her brother John, Augusta Sophia is hard to trace. I did not find her in the 1841 or 1851 censuses, but in 1861, at age 60, she may have been living as a lodger in Wandsworth, Surrey. She may have been living as a lodger in Islington, London in 1871, and she is probably the Augusta Sophia Smithers who died in Croydon, Surrey in 1881.

Rosa Smithers only appears in the records twice: the day she and her sister were baptized as adults, and the day she died, two weeks after her baptism. Everyone must have known she was very ill when she was baptized. She was buried at the Church of St. Mary Edge Hill, near Liverpool, Lancaster, on 8 September, 1827. She was just 24 when she died.

Several months later, in April 1828, her father also died in Liverpool and was buried in the same cemetery.

These highlights are all I know about the lives of Henry and Sophia Smithers’ children. Put them together, though, and patterns start to appear. I have begun to suspect that, although their father wrote of his love for his children in his 1807 book Affection, with other poems, these siblings were not very close. In many of the families I have researched, I have found widows, elderly fathers and unmarried sisters living with other family members. In the case of my Smithers ancestors, this was not the case. I should not speculate, though; I will never learn the truth.

Research Remarks

For more information on other generations of this family, and other families with the same last name, see Michael Smither’s Smither, Smithers, Smythers family tree in Ancestry.com’s Public Member Trees section. http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/49405444/person/12982389958

This article relies primarily on birth, marriage and death records found on Ancestry.com, supplemented by census records as of 184I. I found bankruptcy announcements in English newspapers on findmypast.com.

I have written more extensively about Henry Keene Smithers, non-conformist religious beliefs and apprenticeships. See https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/12/the-apprenticeship-of-coal-merchant.html and https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/12/henry-keene-smithers-non-conformist.html.

The Van Cooten family page, www.vc.id.au/fh/smithers.html, includes several references Martha Keene Smithers and points to the position held by Sydney Smithers.

My suspicion that John Hampden Smithers was named after a politician from the English Civil War era who died in battle in 1643 is based on a poem called Hampden in Henry Smithers’ 1807 book Affection, with other poems. (see https://books.google.ca/books?id=DGUUAAAAQAAJ p.11-12) At first I had no idea who Hampden was. Then, while researching Henry’s political interests, I found an article about John Hampden. Henry mentioned someone named Sydney in the same poem, so perhaps his younger son was also named after a politician.

There was probably only one Augusta Sophia Smithers living in England at that time, so the person I found in the census was probably my ancestor. I was confused, however, because her birthplace was listed as Wandsworth, Sussex. All the information I have about Henry’s family, including property tax records, puts them in Walworth, Sussex.