When my husband and I visited County Durham in northern England in 2009, the guide who drove us around for a day handed me a photocopy of my five-times great-grandfather’s last will and testament, written in 1782.1 I was thrilled!

Our guide, retired genealogist Geoff Nicholson,2 was pleased too. He hadn’t been certain that this will had actually been my ancestor’s, but I recognized the names of the sons and daughters mentioned in it.

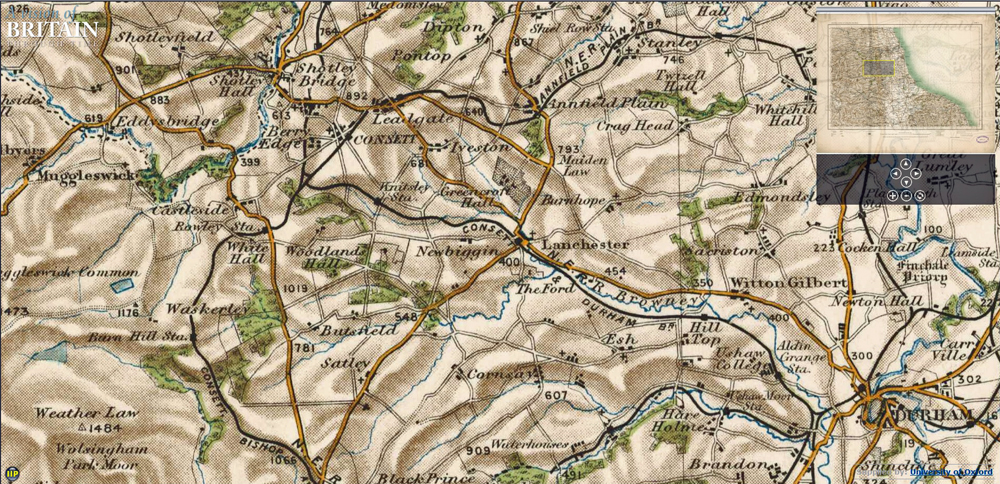

The ancestor in question was Robert Mitchinson, gentleman, of Lanchester Parish, a rural area west of Durham City. Mitchinson, or Mitcheson, is not a common name, but it was fairly common in County Durham, especially two centuries ago. According to a family story, my Mitchinson family came to County Durham from Scotland, however, when they arrived and where they originated are unknowns.

Nor do I know Robert’s date or place of birth, or his wife’s maiden name. One son’s baptism record and another son’s burial record indicate her first name was Mary. Someone named Robert Mitchinson married a Mary Thompson at Durham Cathedral in 1723, but this may not be the right couple.

Robert was probably over 70 years of age when he died in 1784, perhaps closer to 80, and his wife must have also lived a long life since he mentioned her in his will.

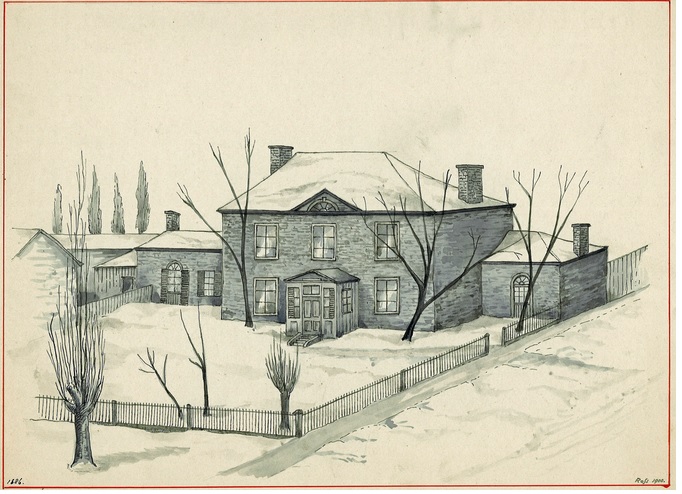

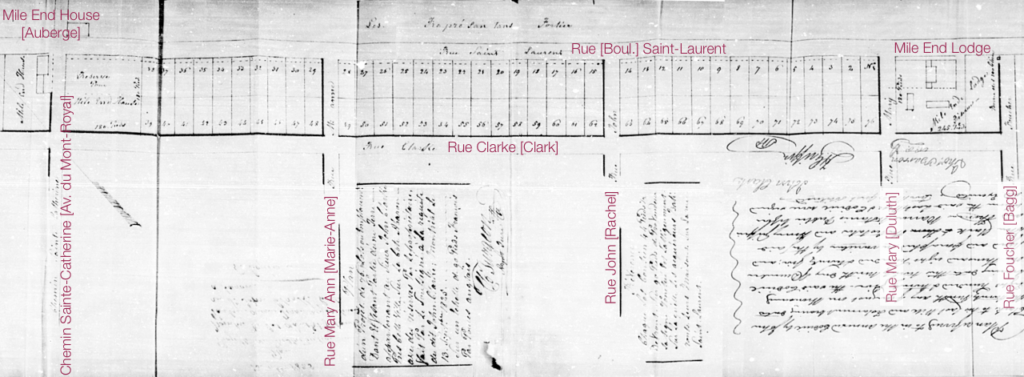

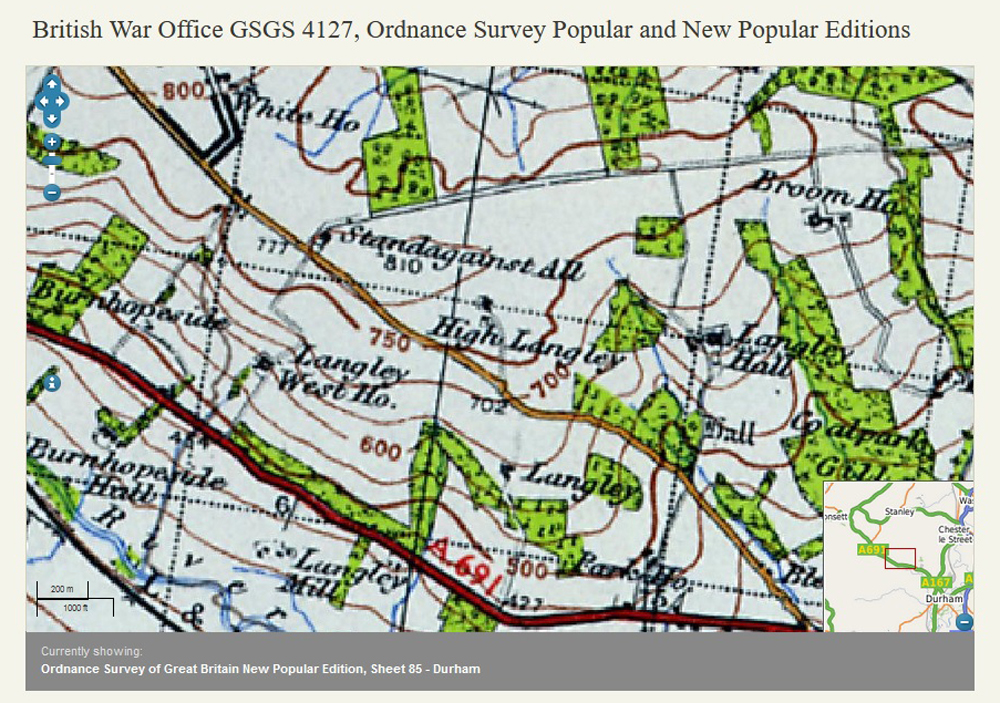

When Robert wrote that will in 1782, he was “of Moorside”, and when he was buried two years later, his residence was identified as Manor House. Moorside is near Consett, northwest of Lanchester village. When the children were growing up, the family lived at High Langley, southeast of Lanchester.

He must have been a farmer since he left his milk vessels to his younger son, Joseph. In fact, Robert was probably what is known as a gentleman farmer who hired people to do the farm work and who owned the property, as opposed to being a tenant farmer.

The Lanchester parish records show that Robert Mitchinson (the babies’ mother was not mentioned), of High Langley, had seven children baptized over an 18-year span: Robert junior was baptized in 1728, Mary in 1730, Jane in 1733, John in 1736, William in 1739, Margaret in 1742 and Joseph in 1746.3 All the children lived to adulthood, although William died in 1763, age 23, and was buried in the cemetery of All Saints Parish Church, Lanchester. According to a family story, John was a captain in the King’s Life Guards, although I have not confirmed that. The others married and lived within about 20 miles of each other in County Durham.

Robert must have thought carefully about his children’s needs as he wrote his will, taking their individual circumstances into consideration. His eldest son was a yeoman farmer in the nearby hamlet of Knitsley, married with two grown sons. Robert senior left him the right to collect the repayment of a 300-pound mortgage loaned to an acquaintance, plus the interest due.

The will referred to Robert’s three daughters by their married names: Mary Taylor, Jane Stephenson and Margaret Taylor. He left one pound to each of them. Presumably their husbands were supporting them comfortably.

To his wife, he left ten pounds and all the household goods and furniture, except for one bed and set of bedcovers which he promised to his youngest son, Joseph. Perhaps Mary lived with a family member after her husband’s death.

Joseph certainly benefited from his father’s estate. He was 37 at the time, married and with three young children, so he probably needed the most help. Unfortunately, the will was not specific enough to be a help to me. It simply said that Robert left to Joseph “all other my Real and Personal Estates whatsoever and wheresoever of what Tenure, Kind or Sort soever the same doth or may consist.”

Robert also left 50 pounds apiece to each of Joseph’s children, to be paid to them when they reached age 21, and to be applied toward their maintenance and education in the meantime. These bequests were no doubt good investments as the two oldest grandchildren eventually immigrated to North America: Robert Mitcheson settled in Philadelphia around 1817 and Mary (Mitcheson) Clark and her husband John Clark came to Montreal around 1795. Another of the grandchildren, William Mitcheson, became an anchor manufacturer and sailing ship owner in London.

Notes and Sources

1. Robert Mitcheson’s will is stored at Durham University Archives and can now be viewed online. Search for it at http://familyrecords.dur.ac.uk/nei/data/simple.php and view it on Familysearch.org. “England, Durham, Diocese of Durham Original Wills, 1650-1857,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-67DQ-481?cc=2358715&wc=9PQL-ZRH%3A1078415794 : 7 July 2014), DPRI/1/1784/M5 > image 3 of 3; Special Collections, Palace Green Library, Durham University, Durham. (accessed Feb. 28, 2022)

2. A former high school teacher turned professional genealogist, Geoff Nicholson was a former president of the Northumberland and Durham Family History Society. He was extremely well informed, not only about the families of the area, but also about the region’s history. He generously assisted me with my research for several years after we met, and I was sorry to learn that he died in 2021.

3. The baptisms and marriages of these family members are online on Familysearch.org, Ancestry and Find My Past.

Sources of Maps:

Ordnance Survey of England and Wales Revised New Series, 1902. Vision of Britain Historical Maps. www.visionofbritain.org.uk/maps/sheet/new_series_revised_medium/sheet_04 (accessed Feb 28 2022)

British War Office GSGS 4127, Ordnance Survey Popular and New Popular Editions, sheet 85-Durham, 1945. VisionofBritain.org.uk (accessed Feb. 28, 2022)