This is the fifth in a series of posts about four generations of my ancestors in colonial Massachusetts and Connecticut. It includes the Bagg, Burt, Phelps, Moseley, Stanley and other related families between 1635 and 1795.

Consider Moseley (1675-1755), of Westfield, Massachusetts had an unusual name. In Puritan New England, where he was born, people normally named their children after close relatives1 or gave them Biblical names, but the origin of Consider’s name is a mystery. Maybe his parents had good imaginations: they called one of his brothers Comfort.

Whatever the meaning and origin of his name, my six-times great-grandfather was born in Windsor, Connecticut, the fifth child of Lieut. John Maudsley (an earlier spelling of the last name) and his wife Mary Newberry. He had five younger siblings, all of them born after the family relocated to Westfield, Massachusetts2 around 1675.

John Maudsley came to New England in 1638 and settled in Dorchester, Mass.3 He married Mary Newberry in 1664 and the couple moved to Windsor. It had been established on the banks of the Connecticut River almost 30 years earlier, and the founding settlers had received land grants but, as a relative latecomer, John purchased his land.

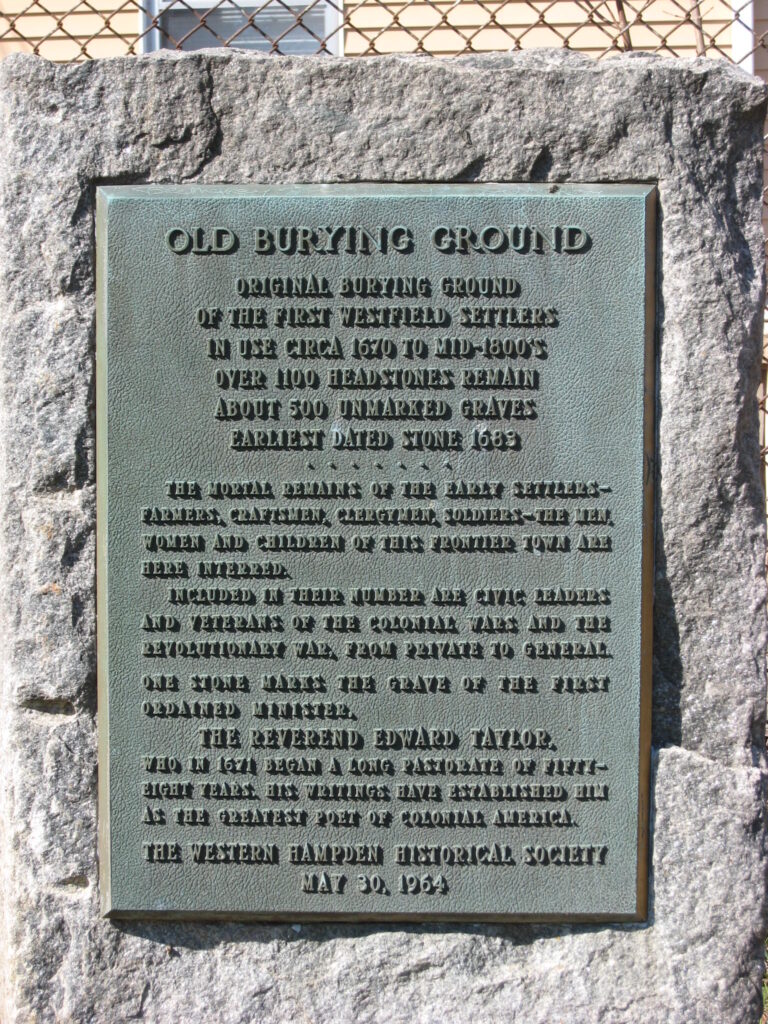

John sold that property in 1677 and moved to Westfield4 where he purchased a house and store. According to Westfield chronicler Chester Stiles, “Mr. Moseley had already proved his valor in battles with the followers of King Philip. [King Philip’s War, 1675-1676, was fought between some of the indigenous people and the colonists.] Hence, he was warmly welcomed to the stockaded hamlet and chosen lieutenant of the little company of defenders. He was also recorded as one of the seven original members, or “foundation men,” of the [Congregational] church first organized under Rev. Edward Taylor in 1677.” 5

John still owned a mill in Windsor, and he died there in 1690. Mary then married her Westfield neighbour, widower Isaac Phelps.6 Consider was 15 at the time of his father’s death and, as one of the older boys in the family, he would likely have been responsible for many chores on the family farm.

Consider was still a young man in 1700 when he was called upon to assist the whole community. Officially, this was peace time, but there was only a lull between two wars between England and France, King William’s War and Queen Ann’s War. Even in peace time, the people of Westfield were worried that the indigenous people who were allied with the French would come from New France (Quebec) and attack them.7

The town residents agreed that several houses should be securely fortified, and Consider’s house was one of the buildings chosen. Teams of neighbours helped with the work. Consider eventually became a lieutenant in the Westfield militia.

Eight Children Including Twins

In 1709, at age 34, Consider married Elizabeth Bancroft.8 The couple had eight children, including twins Elizabeth and Daniel. (Daughter Elizabeth Moseley grew up to marry David Bagg, and they are my direct ancestors.9) Consider’s wife died and, in 1731, he married Rebecka (Williams) Dewey, the widow of Jedediah Dewey II.10 Rebecka had nine children of her own at the time, ranging in age from five to 26.

When Consider died in September, 1755, at age 80, he was described as “one of the wealthiest and most influential men of the town.”11 He may or may not have considered wealth important. Puritans valued hard work, but wasting their money on frivolous things was frowned upon.

Wealth was tied to influence, however. Wealthier residents were usually elected to their town’s most important offices and, every Sunday when the people of New England went to church, where they sat depended on their social status.12

Many Puritans believed that God ordained all that happened, so an individual’s prosperity was a sign of God’s approval for a commitment to godly living. In his will, Consider noted that, “it has pleased God to bless me in this life.”

When Consider wrote his will in January, 1754, he noted that he was “infirm and weak in body, yet of perfect mind and memory.” Indeed, this four-page document shows how well organized he was. He owned numerous tracts of pasture land and farmland around Westfield, and he identified each one according to its geographic location, neighbouring lot owners or the individual from whom he had purchased it.

He had already signed deeds of conveyance giving the titles of several properties to his sons. He split the land between his two sons, Daniel and Israel, and the sons of his late son Benjamin. Each of his five daughters, and Benjamin’s daughter, received relatively small sums of money and a share of his furniture and household goods.

As for his beloved wife Rebecka, his bequest to her was five shillings “in consideration of the articles of agreement concluded between us at our marriage.” He did not describe that agreement,13 but her children probably looked after her for the rest of her life.

Photos by Janice Hamilton

Notes:

Children of John Maudsley and Mary Newberry:

Born in Windsor: Benjamin, b. 1666, m. Mary Sackett; Margaret, b. 1668/69, d. 1678; Joseph, b. 1670, m. Abigail Root; Mary, b. 1673, m. Isaac Phelps Jr.; Consider, b. 1675, m. 1, Elizabeth Bancroft, 2, widow Rebecca Dewey.

Born in Westfield: John, b. 1678, d. c. 1690; Comfort, b. 1680, d. 1711; Margaret b. 1683, m. Samuel Taylor; Elizabeth, b. 1685; Hannah, b. 1690, d. 1707.

Source: Henry R. Stiles, The History of Ancient Windsor vol. II, p. 508.

The Bancroft Family:

Immigrant John Bancroft brought his wife and children to New England in 1632 and settled in Lynn, Massachusetts. After he died in 1637, his wife may have remarried and moved to Windsor, Connecticut.

In 1650, John Bancroft Jr. married Hanna Duper in Windsor. John Jr. and Hanna had five children, including Nathaniel, born 1653. After John Jr. died in 1662, Hanna remarried and moved to Westfield.

Nathaniel Bancroft married Hannah Williams in 1677. They had five children, with Elizabeth, born 1682, being the second-youngest. Elizabeth Bancroft married Consider Moseley in 1709.

Source:

Henry R. Stiles, The History of Ancient Windsor vol. II, p. 40-41.

Children of Consider Moseley and Elizabeth Bancroft:

Rhoda, b. 1710, m. Nathaniel Weller; Israel, b. 1711, Daniel, b. 1714, m. Ann Abbott; Elizabeth, b. 1714, m. Daniel Bagg; Lydia, b. 1716, m. Israel Dewey; Ruth, b. 1717, m. Thomas Root; Mercy, b. 1722, m. Aaron King; Benjamin?, m. Hannah?

Source: Henry R. Stiles, The History of Ancient Windsor, p. 509.

Sources:

- David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, New York, Oxford University Press, 1898, p 23.

- Henry R. Stiles. The History of Ancient Windsor, Vol. II, a facsimile of the 1892 edition, Somersworth: New Hampshire Publishing Co., 1976. p. 508, https://archive.org/stream/historygenealogi02stil#page/508/mode/2up accessed April 10, 2018.

- Robert Charles Anderson, Great Migration Directory: Immigrants of New England, 1620-1640, a Concise Compendium. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2015.

- Henry R. Stiles, The History of Ancient Windsor, p. 508.

- Chester D. Stiles, A History of the Town of Westfield, compiled for public schools from Greenough’s History of Westfield in the Annals of Hampden County and other sources, Westfield: J.D. Cadle & Company, 1919, p. 22. https://archive.org/stream/historyoftownofw00stil#page/22/mode/2up accessed April 14, 2018.

- The American Genealogist. New Haven, CT: D. L. Jacobus, 1937-. (Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2009 – .) https://www.americanancestors.org/DB283/i/12963/239/24672606, accessed April 7, 2018.

- Rev. John H. Lockwood. Westfield and its Historic Influences, 1669-1919: the life of an early town. Springfield, MA, printed and sold by the author, 1922, p. 295, https://archive.org/stream/westfieldandits00lockgoog#page/n324/mode/2up accessed April 10, 2018.

- Massachusetts: Vital Records, 1621-1850 (Online Database: AmericanAncestors.org, New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2001-2016), https://www.americanancestors.org/DB190/i/13251/47/253015607 accessed April 14, 2018.

- Massachusetts: Vital Records, 1621-1850(Online Database: AmericanAncestors.org, New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2001-2016). https://www.americanancestors.org/DB190/r/253018268, accessed April 10, 2018.

- Joann River, River-Hopkins, Saemann-Nickel and Related Families (website), Jedediah Dewey II #8003, http://josfamilyhistory.com/htm/nickel/griffin/sheldon/noble/noble-dewey.htm#jed3, accessed April 15, 2018.

- Lockwood, Westfield and its Historic Influences, p. 386. https://archive.org/stream/westfieldandits00lockgoog#page/n414/mode/2up, accessed April 10, 2018.

- Virginia DeJohn Anderson, New England’s Generation: The Great Migration and the Formation of Society and Culture in the Seventeenth Century, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991, p.175.

- Westfield, Hampden, Massachusetts, Probate Record of the estate of Consider Moseley, 1755. Case Number 102-30, Hampshire Box 102, 1755, page 102-30:1. (Consider’s will is missing from the NEHGS online database of court, land and probate records, however, it is on available on microfilm at the NEHGS in Boston.)