World War II was raging across Europe and the Pacific and the newspaper headlines were dire, but for my mother, the war years may have been the best of her life. After a sheltered childhood, she finally moved out from her parents’ house and found a job. Best of all, towards the end of the war, she met my father.

Joan Murray Smith was born in Montreal in 1918. She grew up an only child and attended a small, all-girls private school a short distance from her house. She was a good student, but shy and unsure of herself.

After finishing high school, she enrolled in art and typing courses. She kept up with her old school friends and there were always lots of parties to attend. In 1937, she and her parents boarded The Empress of Australia and sailed to England and Scotland for a short holiday. It was to be her only trip abroad. Two years later, the war broke out and such vacations became impossible.

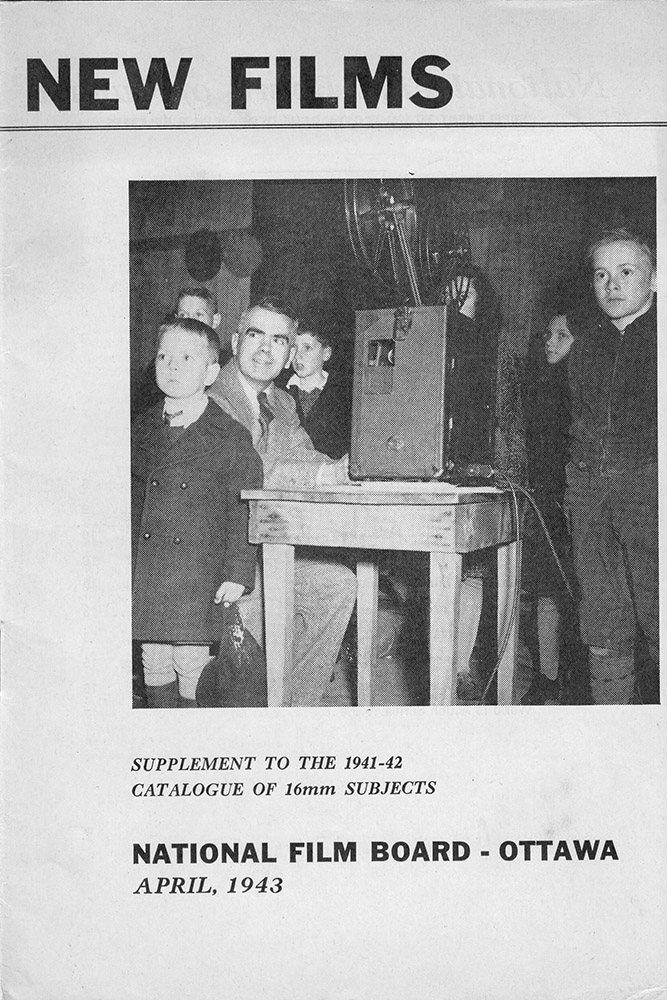

A few years later, Joan joined the war-effort in her usual quiet way: she found a clerical position with the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). At that time, the NFB was in its infancy. It was headed by John Grierson, a Scottish-born pioneer in documentary film-making, and my mother was thrilled to work there. She later told me that she helped set up the film library at the film board. She was well-organized, and no doubt she found the job both interesting and rewarding.

Many of NFB’s early films were morale-building movies focused on Canada’s role in the war.

They also produced documentaries informing people about civilian defence and the roles of different branches of the armed services. Other films were short educational documentaries about food and agriculture, and there was a series of films targeted at women to help homemakers deal with shortages of consumer goods. These were shown in movie theatres across Canada, while libraries made them available to school and church groups. In rural areas, they were shown in community centres, using travelling projectors supplied by the NFB.

The NFB’s head office was located in Ottawa, a two-hour train trip from Montreal. Joan lived with her friend Denny and Denny’s father for a year, then she moved into a house with several other young women. Using the office typewriter, she wrote to a friend, “I am enjoying myself hugely. I got caught up in a round of small gaiety and am finding housekeeping wonderful fun. Not that I do anything but wash up as all the other girls have earlier hours than I do and always have the food ready for me at breakfast and dinner, which is very lucky for all concerned.”

Ottawa is a quiet city, but it was probably more interesting during the war. One of its chief advantages for a young single woman was that it was full of officers. As Joan wrote in another letter, “I have discovered a very nice captain whose chief virtue is that he is a wonderful dancer, but who unfortunately isn’t stationed here.”

Then she met Jim Hamilton, her husband-to-be. He too was working for the NFB. He had a science background and was making a film to educate members of the armed forces about sexually transmitted diseases.

Intelligent and something of a non-conformist, Jim was shy with women, while Joan was looking for someone different from the conservative sons of wealthy Montreal families she had grown up with. My vision of my future parents in their dating days comes from a photo, taken in the Gatineau hills on what looks to be a warm day in early spring 1946 in which they looked happy and carefree.

This article is also posted on https://genealogyensemble.com