It was one of the highlights of Montreal’s social calendar. The marriage of Clara Smithers to Robert Stanley Clark Bagg took place on June 8, 1882, at St. Martin’s Anglican Church, and the church was filled with what The Gazette reporter called “the elite of our inner social circles” long before the bride and groom arrived for the eleven o’clock ceremony.

“The bride’s dress was a rich and handsome one of white brocaded satin, with the traditional veil of costly lace,” the reporter noted. That veil of Irish lace was the same one worn by Clara’s mother, Martha B. Smithers, and later by Clara’s daughters.

Clara must have been flustered, or perhaps she was just thrilled to be a married woman. In the church registry, she signed her name as Clara Bagg, rather than using her maiden name. Fortunately, the minister recorded the marriage correctly.

Following the service, the wedding party drove to the residence of the bride’s father on University Street, where lunch was served. The newlyweds then left by train for Quebec City, where they boarded the SS Parisian for a two-month honeymoon in Europe.

Clara was the daughter of Charles Francis Smithers, an English-born banker. The eighth of eleven children, she was born in Montreal in 1860, but her father’s work took him to New York City, and Clara spent much of her adolescence in Brooklyn. The family returned to Montreal in 1879 and her father was named president of the Bank of Montreal two years later.

Stanley was born in 1848, the son of Stanley Clark Bagg, one of Montreal’s largest landowners, and Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, originally of Philadelphia. Like his father and grandfather, R. Stanley Bagg went by the name Stanley. He studied law at McGill and, after his father died in 1873, Stanley took over the administration of the family properties, overseeing rentals and sales.

I do not know how they met, but there must have been many opportunities for young women to meet bachelors in their social circles. One day, Stanley wrote a short poem with a religious theme in Clara’s autograph book. It was more about loving God than loving her, but it did the trick.

For the first years of their married life, Clara and Stanley lived next door to his mother’s house, Fairmount Villa, on Sherbrooke Street near Saint Urbain. Their first two children were born there: Evelyn St. Clair Stanley Bagg in 1884, and Gwendolen Catherine Stanley Bagg (my grandmother) in 1887. Harold Fortescue Stanley Bagg was born in 1895, after the family had moved to a more fashionable neighbourhood.

Stanley had a new house built around 1891. Made of red sandstone imported from Scotland, it was at the corner of Sherbrooke Street and Côte des Neiges Road, at the edge of the area known as the Golden Square Mile. Stanley died in Kennebunkport, Maine in 1912, and the widowed Clara lived in that house until her death in 1946.

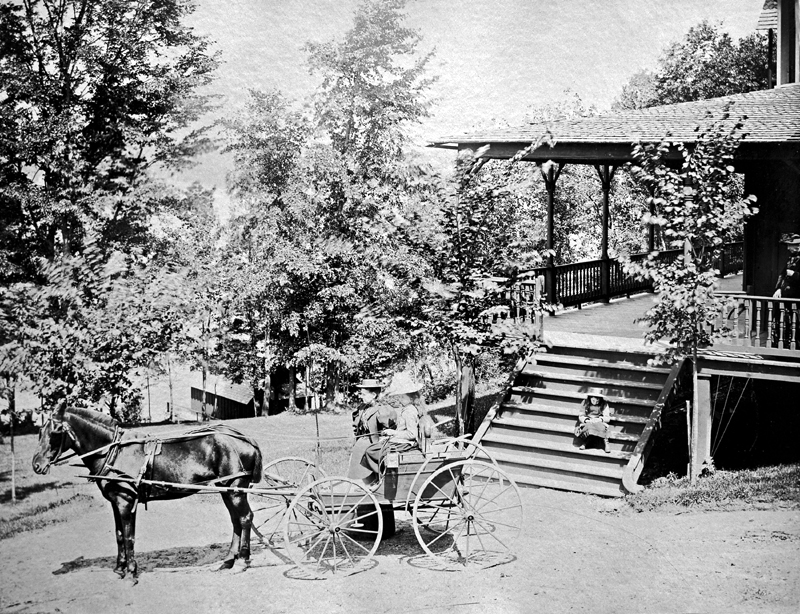

Photo credit: McCord Museum. http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca/en/collection/artifacts/II-66752.1

Research Remarks: The article about the wedding appeared in The Gazette, 9 June, 1882, page 3. Thanks to Justin Bur for finding it. http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=Fr8DH2VBP9sC&dat=18820608&printsec=frontpage&hl=en.

The image of the church registry can be viewed at http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?ti=0&indiv=try&db=drouinvitals&h=13847196. Source: Ancestry.com. Quebec, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1967. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008. Original data: Gabriel Drouin, comp. Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin.

Clara’s branch of the family is included in the Smithers Family Book, by Elizabeth Marston Smithers, produced by the Institute for Publishing Arts, 1985. This book provide a good starting point, although there are some errors and omissions in the early generations.

I have not yet found baptismal records for Clara or her siblings, although I haven’t looked very hard. According to the records of Mount Royal Cemetery, her date of birth was 4 Feb. 1860.

Like most big cities, Montreal had a city directory that makes it possible to track the family’s home address and Stanley’s work address every year. Lovell’s Directory can be searched online at http://bibnum2.banq.qc.ca/bna/lovell/.

Clara’s autograph book is in private hands.