There is a big gap in my three-times great-grandmother’s story. Mary Frances (Fanny) MacGregor was born in Scotland around 1790, and she lived her adult life as a wife and mother in Philadelphia, so when did she come to America, and why?

Fanny was born in Port of Menteith parish, Perthshire and, according to family lore, she finished her education in Edinburgh. She was then said to have come to the United States with her brother John. I have not, however, been able to confirm that she had a brother named John, and I have not yet found Fanny’s name under any spelling on a passenger list arriving in the United States.

One possibility is that she was with “Mrs. McGreger and family,” arriving at the Port of Philadelphia in 1815. Or perhaps she had married in Scotland, came to America with a first husband and then found herself a widow. If she came with her brother, family members probably felt they would have a better future in America than in Scotland and arranged for their passage.

I have not yet found her marriage record, but she was married by 1818 when her eldest child was baptized. Her husband was Robert Mitcheson, born in 1779 near Durham, England. He had started his career in England as an iron manufacturer and came to the United States by way of Antigua. In his 1820 application for naturalization, he described himself as a distiller, but by the mid-1830s he was a “gentleman.”

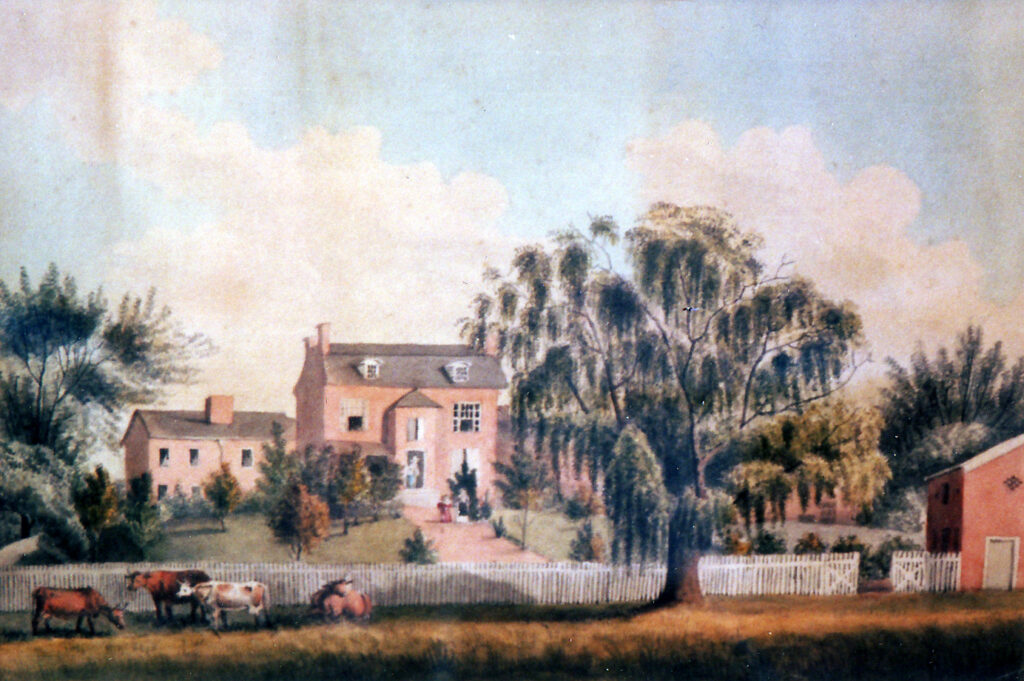

Philadelphia city directories indicate the Mitcheson family lived on Coates Street (later called Fairmount Avenue) in Spring Garden, a primarily rural township north of the city. They owned a large lot, about the size of half a city block, and called their home Monteith House in memory of Fanny’s birthplace. But Philadelphia was quickly becoming an industrial powerhouse, and Spring Garden’s population grew from 3,500 to 28,000 between 1820 and 1840. A huge penitentiary and the Fairmount water reservoir were constructed near the Mitcheson home, and railroads and paved turnpikes appeared.

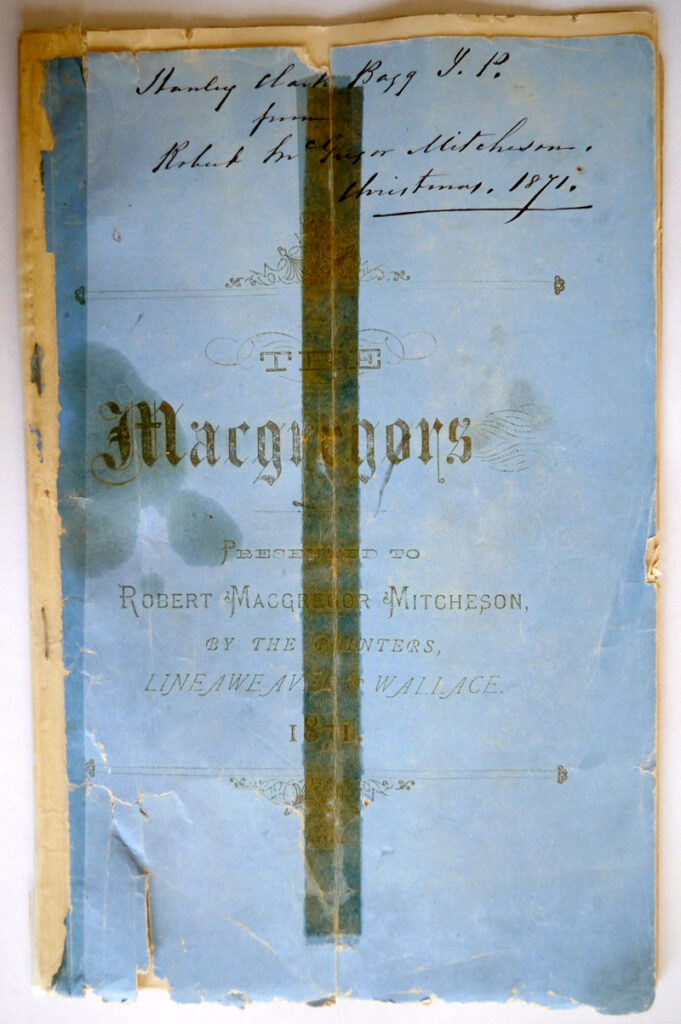

Fanny was in her late 20s when she married, and Robert was 10 years her senior, but that did not stop them from having a large family. According to the records of St. John’s Episcopal Church in neighbouring Northern Liberties township, their oldest child, Robert MacGregor Mitcheson, was baptized in 1818. Catharine, my future great-great grandmother, was baptized in 1822. Sarah Frances, born in 1826, was very ill when she was baptized and died shortly thereafter, aged four months. Duncan MacGregor arrived in 1827, Joseph MacGregor (who later reversed his given names and went by McGregor J. Mitcheson) was baptized in 1830, and Mary Frances in 1833. One last child, Virginia, born in 1836, did not survive.

I have the impression from reading their wills and other documents that the Mitcheson children had strong personalities and that sibling rivalry extended into adulthood, but that is another story. In her portrait, Fanny has a bit of a twinkle in her eye, so perhaps the children inherited their spirit from her.

Robert Mitcheson died in 1859. Fanny died three years later of “valvular disease of the heart,” according her death certificate. They are buried together in the family plot at St. James the Less Episcopal Church.

Photo credits: both are in private collections. The caption was updated April 11, 2020, confirming that the painting shows Monteith House.

Edited June 3, 2014 to correct Catharine’s year of birth.

Research Remarks:

For my blog entry about researching the Mitcheson family on historic maps, see http://genealogyensemble.com/2014/03/29/mapping-the-mitchesons-of-philadelphia/

The port of Philadelphia was an extremely busy place, although New York outstripped it in the early 1800s. Located on two navigable rivers, the Delaware and the Schuylkill, Philadelphia’s merchants traded with Europe, China, the West Indies and other east coast ports. Philadelphia passenger arrivals are listed on Ancestry.com.

Robert Mitcheson’s family appeared in the U.S. Federal Census in 1830 in the Spring Garden district, but the census does not reveal much information about them. City directories are more helpful, listing the head of the household, address and occupation. Directories generally appeared every couple of years, and they can be searched by street address or by family name. They also included advertisements for local businesses and often listed government officials and people involved in community organizations. Some digitized Philadelphia directories are available on the http://www.philageohistory.org/geohistory/website, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) has a collection of specialized directories: http://hsp.org/collections/catalogs-research-tools/subject-guides/philadelphia-city-directories

I could not find the baptisms of the Mitcheson children online. Finally, I found them when I visited the HSP library. The children were all baptized at St. John’s Protestant Episcopal Church, Northern Liberties, Philadelphia. The HSP has the church’s records for Births 1815-1917, Marriages 1815-1916, Deaths 1851-1916. The church, designed by architect William Strickland, was constructed in 1815. Today it houses Holy Trinity Romanian Orthodox Church, and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

I have been deliberately vague about Fanny’s age. There is a baptismal record in Scotland indicating that Mary Frances MacGregor was born in 1789, but according to her headstone, she was born in 1792. Either she lied about her age, or a first child died and my Mary Frances was another child given the same name. She died Sept. 29, 1862.