Many genealogists are aware that the Montreal’s McCord Museum has a large collection of digitized photographs taken in the 19thcentury studios of William Notman (1826-1891). Although it is best known for its photographs of Montreal’s English-speaking elite, the collection goes far beyond the studio, including pictures of Montreal’s Victoria Bridge, the Canadian Pacific Railway, First Nations people across the country and ordinary Montrealers at work and at leisure.

This is only one image collection of potential interest to genealogists researching Montreal. As you try to try to imagine the people and places that would have been familiar to your ancestors in what was once Canada’s largest city, here are some other resources that might inspire you.

The place to start exploring the McCord Museum’s images is http://www.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/keys/collections/. This page links to the museum’s online collection of more than 122,000 images, including paintings, prints, drawings and photos. There are documents such as diaries, letters and theatre programs, as well as costumes and archaeological objects. While the museum’s collections focus on Montreal, they include images and objects from the Arctic to Western Canada and the United States. You can search the McCord’s online collection for an individual name, or you can browse time periods, geographic regions and artists.

The McCord also has a flickr page, https://www.flickr.com/photos/museemccordmuseum/albums.The historically themed albums on the flickr page include old toys, Quebec’s Irish community and an homage to women.

The Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) is another excellent source of digital images, including photographs, illustrations, posters (affiches) and post cards (cartes postales) from the past. To start exploring these collections, go to http://www.banq.qc.ca/collections/images/index.html.

There are two collections of special interest to people with Montreal roots. The first is a collection of 22,000 photos taken by Conrad Poirier (1912-1968), a freelance photojournalist who worked in Montreal from the 1930s to 1960. He covered news (nouvelles), celebrities, sports and theatre, and he did family portraits, weddings, Rotary Club meetings and Boy Scout groups. I even found a photo of myself at a 1957 birthday party (fêtes d’enfants). You can search (chercher) the collection by subject or by family name.

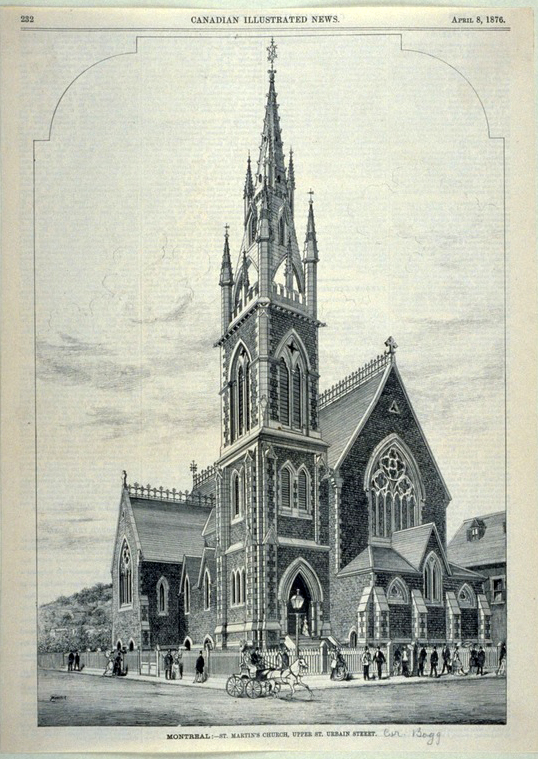

The other collection of interest to people researching Montreal is the BAnQ’s Massicotte collection (http://www.banq.qc.ca/collections/collection_numerique/massicotte/index.html?keyword=*). Edouard-Zotique Massicotte (1867-1947) was a journalist, historian and archivist. The online collection mainly consists of photos and drawings of Montreal street scenes and buildings between 1870 and 1920. Some illustrations come from postcards, while others are clippings from periodicals. There are also a few blueprints and designs. The accompanying text is in French. You can search this collection by subject, by location, date of publication or type of image, or you can put in your own search term.

Philippe du Berger’s flickr page https://www.flickr.com/photos/urbexplo/albums is a gold mine of Montreal images. He includes contemporary photos of the city, including neighbourhoods that have recently been changed by big construction projects such as the new CHUM hospital. There are old photos of neighbourhoods such as Griffintown, Côte des Neiges and Hochelaga-Maisonneuve and he illustrates the transformation of the Hay Market area of the 1830s that eventually became today’s Victoria Square. Some albums include old maps to help the viewer put locations into geographic context.

The City of Montreal Archives has uploaded thousands of photos to its flickr page, https://www.flickr.com/photos/archivesmontreal/albums/. They are arranged in albums on various topics, ranging from city workers on the job to lost neighbourhoods, newspaper vendors, sporting activities and cultural events.

Photos:

James Duncan. Montreal from the Mountain, 1830-31. M966.61, McCord Museum. http://collection.mccord.mcgill.ca/en/collection/artifacts/M966.61?Lang=1&accessnumber=M966.61

Conrad Poirier. Cathy Campbell’s Party, 1957, P48,S1,P22510, BAnQ. http://www.banq.qc.ca/collections/images/notice.html?id=06MP48S1SS0SSS0D0P22510

Rue St-Urbain [image fixe], 1876, BAnQ. http://collections.banq.qc.ca/bitstream/52327/2084185/1/2734179.jpg

This article is also posted on https://genealogyensemble.com.