My great-grandmother was born twenty years before Canada became a country, and she died on the eve of World War II. Over the ninety years of her life, society went through many great changes, but Mrs. Murray Smith lived in her own world.

Born in 1847, Jane Mulholland was the daughter of Henry Mulholland, an Irish-born Montreal hardware merchant, and Ann Workman. She grew up with three brothers and a sister in a two-story house on Sherbrooke Street. Today, that location is in the heart of Montreal, the site of the Ritz Carlton Hotel, but when Jane was a child, she lived on the city’s outskirts, surrounded by fields, cows and horses.

I don’t know how Jane met her future husband. At the time, he lived in Peterborough, a small city in eastern Ontario, where he worked for the Bank of Toronto. It would not have been proper for her to pursue him herself so, according to a family story, her nanny wrote to tell him he had an admirer in Montreal. Jane married 33-year-old John Murray Smith at St. George’s Anglican Church in Saint Anne de Bellevue, at the western end of Montreal Island, in 1871.

Their first two children were born in Peterborough: Henry in 1873 and Louise in 1875. May (born 1877), Fred (1879), Ella (1881) and Mabel (1884) were born in Montreal after John was promoted to manager of the Bank of Toronto’s branch there. In 1881, the family bought a house on McGregor Street, high on the slope of Mount Royal. At that time the mountain was being developed as a newly fashionable part of the city.

Many years later, my mother described her grandmother’s two-storey stone house with its big back garden. She recalled black leather furniture in the study, a roll-top desk and a stuffed owl under glass. The living room had red velvet curtains, walls covered with gilt-framed, gloomy paintings and an elaborately carved “what-not,” its mirrors reflecting dangling china cupids.

In 1891, seventeen-year-old Henry died of appendicitis. John died of a heart attack three years later. After just 23 years of marriage, Jane was a widow, but she was not alone. Daughter Louise lived at home until she married in 1906. Fred (my grandfather) moved out when he married in 1916, but he continued to advise his mother on investment decisions. The three younger daughters did not marry. Kate, the Scottish-born live-in cook, kept the Murray Smith family well fed for many years.

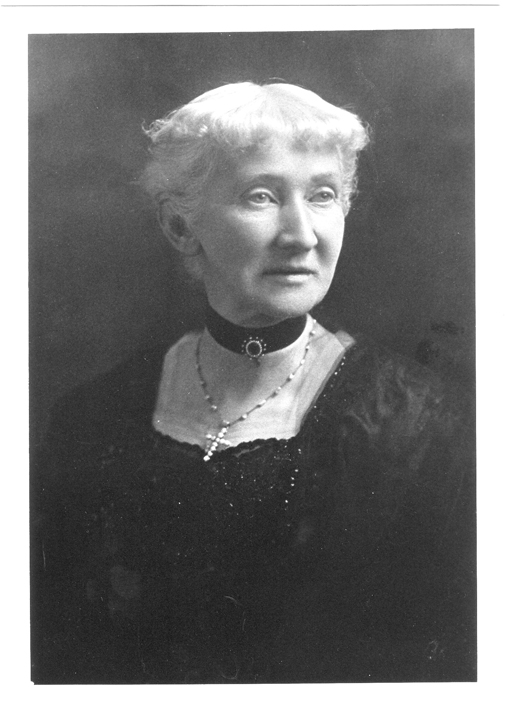

My mother recalled childhood visits in the 1920s: “Granny was a tiny old lady dressed in black; presumably she was forever in mourning for her husband. She always wore a black velvet ribbon pinned around her neck.”

Despite her attire, Jane does not seem to have been unhappy. Her grandchildren often came to tea in the garden or to go tobogganing. My mother wrote, “I think of Granny at Christmas parties, surrounded by five noisy grandchildren, plus numerous older relatives, a passive spectator at the games we played, but always joining in with her laughter and making us feel she was one of us.”

For the last ten years of her life, Jane was bedridden, felled by a stroke or dementia, and May, Ella and Mabel looked after her. My mother recalled, “She lay shriveled in the huge bed with its ugly high carved wooden headboard, pink bows in her hair, her three daughters hovered over her. Each time she babbled incoherently, one of the aunts bent over solicitously, took her hand and said ‘What is it, dear?’” When Jane’s eldest daughter, Louise, succumbed to cancer in 1935, Jane did not even understand that she had died.

Jane died in August 1938, age 91, and is buried in Mount Royal Cemetery with her husband and five of her six children.

Photo credits:

Mrs. J. Murray Smith, photo courtesy Benny Beattie

Murray Smith gravestone, by Janice Hamilton

Notes:

My mother was very fond of her father’s three spinster sisters and, in the late 1970s, she wrote an article called “Three Sisters: a Memoir.” It was published in a community newspaper called The Townships Sun, however, the quotes I have used come from her typed manuscript.

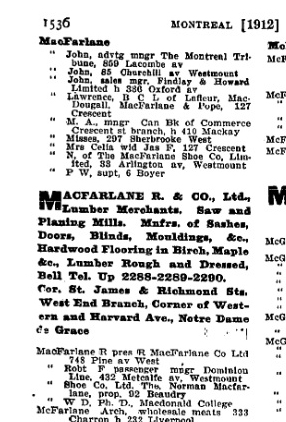

Because Smith was such a common name, the family used Murray Smith as if it was a hyphenated last name. Directory listings are under Smith. I used Lovell’s Directory of Montreal to find the family’s location in Montreal. Jane is difficult to find in the census of Canada. I think she identified herself as Mrs. J. Murray Smith, but Ancestry.ca transcribed that as Wilhelmine. It is easier to look up the family under the names of her daughters, May, Ella or Mabel Smith.

I have not yet found Jane’s baptismal record online. Her date of birth, 18 June 1847, and her date of death, 18 Aug. 1938, are on her gravestone in Mount Royal Cemetery. Her marriage on 4 Oct. 1871 is included in the Drouin Collection records on Ancestry.ca.

After the family home at 1522 McGregor Street was sold in the 1950s, it was torn down and a highrise apartment building was built on the site.