The itinerary of my grandparents’ 1906 honeymoon reads more like a business trip than a romantic vacation, nevertheless, they both seemed to enjoy their trip to Chicago, Toronto and Montreal.

My future grandfather was planning on running for election to the school board, so he wanted to research schools, and my grandmother wanted to shop for things she couldn’t find in stores at home. Meanwhile, both were interested in medicine, so several hospital tours were on the agenda.

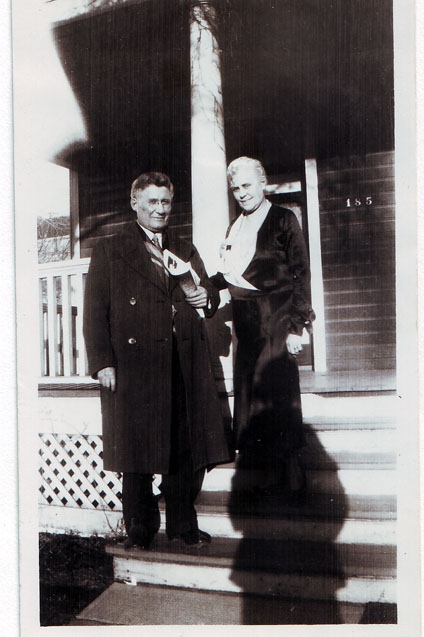

The bride and groom were Dr. Thomas Glendinning Hamilton, 33, a Winnipeg physician, and Lillian May Forrester, 26, a nurse. Lillian had trained at the Winnipeg General Hospital and graduated in May, 1905 with the class prize for highest general proficiency. They met at the hospital and she resigned when they became engaged.

According to a newspaper account, the wedding took place at the Winnipeg home of the bride’s uncle, lawyer Donald Forrester, at 4:30 p.m. on Nov. 26, 1906: “The bride, who wore a pretty gown of white net over taffeta and carried bride’s roses, was given away by her father, Mr. John Forrester, of Emerson…. There were no attendants, only the immediate relatives of the happy couple being present.” Following the brief Presbyterian service, the bride quickly changed into a red and grey travelling outfit and they left for their honeymoon on the 5:20 train.

Lillian kept a diary of the wedding trip, leaving out any romantic details, which is probably why that account is available for all to read at the archives of the University of Manitoba.

They spent their wedding night on the train to St. Paul and reached Chicago late the following evening. Staying at the 16-story Great Northern Hotel, they visited the Marshall Field’s department store, viewed the impressive tower of the Montgomery Ward Building and attended a play. They also visited the 1,400-bed Cook County Hospital which, Lillian noted, treated 25,000 patients a year and did an average of 10 operations per day. They then headed by train to Detroit for a brief stopover, and to Toronto, where they began exploring the neighbourhood around Queen’s Park and the University of Toronto.

Niagara Falls was on their honeymoon bucket list. T.G. and Lillian spent a snowy day there, seeing both the Canadian and American falls. Dressed in waterproof clothing, they viewed the back of the falls, and they took a cable elevator car to see the Whirlpool Rapids and have photos taken. Back in Toronto, they stayed two nights with T.G.’s Aunt Lizzie Morgan, then boarded a train for Montreal.

Lillian noted some of the towns they passed on that leg of the journey, including Belleville and Shannonville. She did not add in her note book that her family lived in this region before moving to Manitoba in the early 1880s, and that she had been born near Belleville. It was now early December, and there was a heavy snowfall in Montreal, nevertheless they walked down St. Catherine Street and took the street car to Notre Dame Cathedral, which they found to be “as grand and beautiful as we anticipated.” Lillian ordered 50 visiting cards – she would need them in her new social role as the wife of a busy physician – and she visited several stores “and spent her first pin money.” She described Morgan’s department store as “the most beautiful store we have ever seen. The art gallery, glass room, electrical room and furniture department are all exceedingly fine.” Meanwhile, T.G. interviewed the Superintendent of Schools in Montreal.

No visit to Montreal is complete without a trip up Mount Royal, and T.G. and Lillian went to the top “in a warm red sleigh, had a splendid view of city, canal, river and Victoria Bridge.” On the way back downtown, they visited the Royal Victoria Hospital, ”a beautiful, well equipped building” with 300 beds. The next day they explored the Redpath Museum, had dinner at the Windsor Hotel (one of the city’s best) and took the overnight train back to Toronto. Again they stayed with Aunt Lizzie. It was a Sunday so, after church, T.G.’s cousin accompanied them to visit more relatives. The following day, T.G. met with the Superintendent of School Buildings in Toronto and with a former principal of Wellesley Public School, said to be the most handsome and modern school building in Toronto.

Over the next few days they visited more extended family members and went to see St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Scarborough, where T.G.’s father and grandparents were buried. They also visited the Scarborough farmhouse where T.G. had spent his childhood. They stayed downtown on their last two days in the city, and attended a lecture on new developments in vaccines. Finally, they headed west on the night train to Chicago and Minneapolis. When they arrived back in Winnipeg, Lillian’s brother picked them up at the station and they went to buy furniture.

The last entry of the wedding trip diary was dated three days before Christmas 1906, and almost one month had passed since their wedding: “Dec. 22. Had tea at 8 a.m. in our own house.”

Sources:

Lillian Hamilton, “Wedding Trip,” University of Manitoba Archives and Special Collections, Hamilton Family Fonds, Hamilton Family – Personal; Box 1, Folder 1.

Note: a slightly shorter version of this story is posted on the collaborative blog, https://genealogyensemble.com