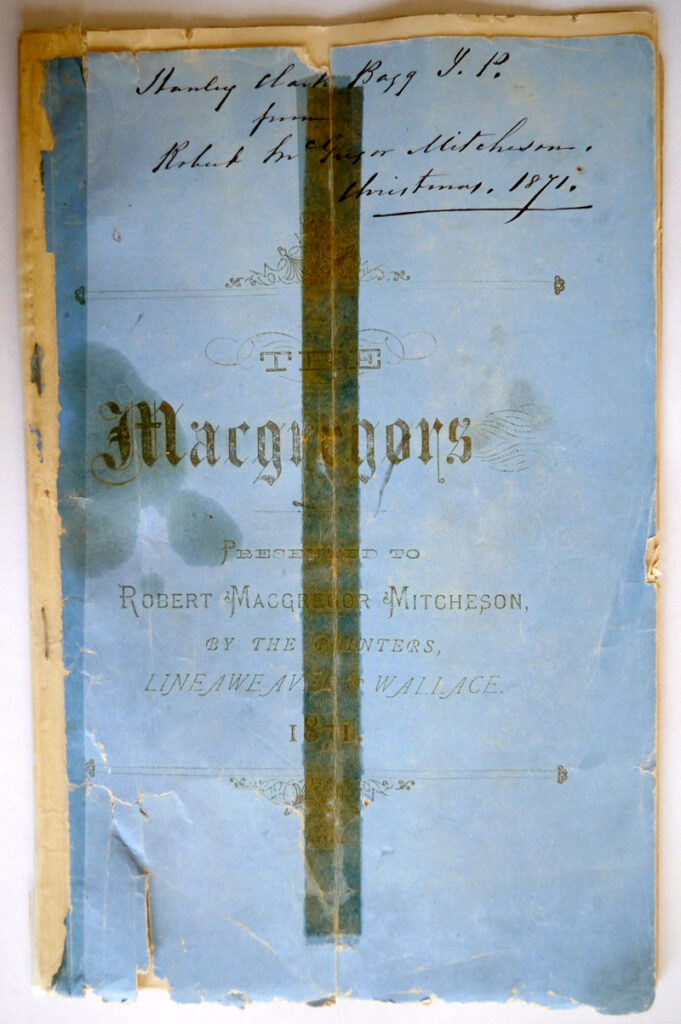

As a genealogy beginner, I thought I knew all about Fanny MacGregor’s family history. Family lore had it that Fanny, my three-times great-grandmother, (c.1789-1862) was descended from the chiefs of the MacGregor clan. I had inherited a copy of a booklet, printed in 1871, that supposedly described those ancestors, tracing back to the early kings of Scotland.

I read the booklet carefully until I got to the last page. Then it claimed that Peter MacGregor “had several children, among whom was Duncan MacGregor…. Duncan had a daughter Fanny ….” After pages of detailed pedigrees based on oral records, this was suddenly too vague to be credible.

I have confirmed that Fanny’s father’s name was Duncan MacGregor, but that was a very common name at the time and I have been unable to identify his baptismal record. Then I contacted the Clan Gregor Society in Scotland and learned that Peter MacGregor, Fanny’s grandfather according to the booklet, had only one child, and that child had no descendants.

I realized that the booklet was a history of the MacGregor chiefs, with one paragraph about Fanny at the end and no solid evidence to tie her to them.

Furthermore, the family stories I had heard from my mother never mentioned anyone named Peter. Her stories said that Fanny was born near Stirling, Scotland (that was true) and was descended from Evan Murray MacGregor, a Jacobite officer during the rising of 1745 led by Bonnie Prince Charlie. Fanny’s ancestor was said to have had a price upon his head after he escaped from Edinburgh Castle. At some point, the story added, a baby was lowered in a basket from the castle. I loved these romantic images, but what was true?

I started to read more about the history of Clan Gregor. Members of a Scottish clan were not all related; the clans were more like extended families, and included people who owed allegiance to the chief. There were four principal families in Clan Gregor in the 17th century, one being the Glencarnaig line, at that time mainly tenant farmers in the Balquhidder area of Perthshire. Members of the Glencarnaig family have been Gregor Clan chiefs since 1774.

There were bitter feuds between Clan Gregor and other clans, and the MacGregors lost their ancestral lands to more powerful neighbours around 1600. As a result, they fell out of favour with the king. The government passed a law abolishing the name MacGregor; anyone who used that name could be put to death. Off and on between 1603 and 1774, some members of the Glencarnaig family used the alias Murray.

Meanwhile, many people in Scotland, especially in the Highlands, were unhappy with the king in faraway London. When Charles Edward Stuart, or Bonnie Prince Charlie, came to Scotland in 1745 to raise an army and try to seize the throne he claimed was his birthright, he found many supporters. They were called Jacobites. The Jacobites had some military success at first, but were completely crushed the following year at the Battle of Culloden.

Several hundred members of Clan Gregor fought for the cause. Robert Murray MacGregor of Glencarnaig was a Lieutenant-Colonel during the rising. He went into hiding after Culloden, but surrendered in 1747 and spent three years in Edinburgh Castle. His brother Evan was an aide de camp to the young prince.

After Culloden, government soldiers punished the Highlanders, burning their homes and taking their livestock. In an attempt to wipe out the traditional Highland clan system, the government banned people from wearing tartans and from carrying weapons from 1747 until 1782.

Fanny MacGregor was born just a few years after that ban was lifted. Whether or not she was related to the clan chiefs, to Peter, or to Evan, she must have heard about these events and they must have had a profound impact on her. She left for America and married an Englishman, but she never forgot the stories she heard about the banning of the MacGregor name, about the imprisoned Jacobite officer, and about the suffering of the Highlanders in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising.

All three of Fanny MacGregor Mitcheson’s sons, Robert, Duncan and Joseph, had MacGregor as a middle name. Eleven years after her death, Robert MacGregor Mitcheson gave the booklet about the MacGregor chiefs to his brother-in-law in Montreal, Stanley Clark Bagg.

At first I took that booklet to be factual family history, then I questioned its credibility when I realized there were holes in the genealogy. Now I recognize its value as part of the family’s heritage.

Photocredits: Janice Hamilton

Research remarks: The MacGregors called themselves Children of the Mist because they felt persecuted. Their history is also hidden in the mists of time, and I may never discover the truth about Fanny’s pedigree. Every family has stories, however, and it is important that genealogists and family historians try to untangle the myths from the realities.

Here are some sources I used:

www.clangregor.com The website of The Clan Gregor Society includes a history of the clan, a list of associated family names, news about clan gatherings and information about a DNA study.

www.glendiscovery.com/macgregor45.htm “The Clan Gregor in the last Jacobite rising of 1745-46,” by Peter Lawrie, 1996.

Seton, Bruce Gordon, Sir. The prisoners of the ’45 / edited from the state papers by Sir Bruce Gordon Seton (Bart.), and Jean Gordon Arnot. Edinburgh: Printed by T. and A. Constable ltd. for the Scottish history society, 1928-29. (I found this book in the McGill University library.)

http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/content/help/index.aspx?1161 One of the most famous MacGregors was Rob Roy MacGregor, 1671-1734 . He became a legend, but he was a real person. As far as I know, he was not related to my ancestors.