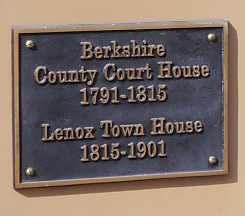

Last spring, my husband and I travelled to Pittsfield, in western Massachusetts, where Phineas Bagg (c 1751-1823), my four-times great-grandfather, lived. As we wandered around the nearby town of Lenox, we spotted a sign indicating that a small office building had once been the Berkshire County Courthouse.

Simply by chance, we were standing in front of the building where my family’s history had taken a dramatic turn.

In 1794 and 1795, my ancestor appeared in that courthouse because he owed local merchants money he couldn’t pay. After he lost most of his land to pay off these debts, he left Massachusetts for good.

Phineas did not have an easy life. He was born in Westfield, MA around 1751, the youngest of eight children of farmer David Bagg and his wife Elizabeth Moseley.1 His mother died when Phineas was about eight years old and his father remarried, but that second wife also died. In the mid-1760s, the family moved to Pittsfield, a new town on the western frontier of Massachusetts, and David Bagg remarried a third time.

The family cleared the forest so they could plant crops and likely built their own log cabin. As a young single man in 1777, Phineas purchased a farm of his own of about 100 acres.

Although Pittsfield was remote, the political events of the time were of great interest to its residents and opposition to Great Britain was strong. When the American Revolution (1775-1783) broke out, Phineas, his father and several of his brothers served as a soldiers. On three occasions, Phineas marched in a local militia unit, and he served in the Continental Army for about a month.2

By the time the war ended, Phineas had his own family. In 1780, when he was about 29, he married 20-year-old Pamela Stanley.3 There are no records of their children’s births or deaths, but Phineas and Pamela had four children who survived to adulthood: Polly, Stanley, Abner and Sophia.4

When his household was counted in the 1790 United States census, it included six people: one white male age 16 and older, two white males under 16 and three white females.5 Phineas Bagg’s name also appeared in other Berkshire County records. His household was included in a 1786 local census, his name appeared in the ledger of a local merchant between 1791 and 1794, and he paid $49.11 in real estate tax in 1795.6

What was not recorded was his wife’s death. Pamela probably died between 1792 and 1794, a period when there were many deaths in the community. This would have been a hard blow to the family, not only emotionally, but also because women usually contributed to the work on the farm.

Farmers Under Pressure

Many New England farmers had faced financial difficulties ever since the end of the revolution. In 1886 and 1887, many of them joined in what became known as Shays’ Rebellion.7 I do not know whether Phineas joined the rebels, but he shared a similar financial situation.

Phineas was a yeoman: a farmer who owned his own land. Land ownership gave yeomen a great deal of pride and independence. Before the revolution, the farmers in the interior regions of Massachusetts were subsistence farmers: they grew enough crops to feed their families (mostly Indian corn, apples and vegetables) and bartered the small surplus of goods they produced with local merchants to obtain products such as nails and sugar.

After the revolution, new economic forces squeezed the merchants, and they in turn pushed their customers for cash. The farmers did not have cash, so the merchants took them to court. Many yeomen lost their land as a result, others were sent to jail – and jail was a dirty and dangerous place.

This was exactly what happened to Phineas, although his troubles took place a few years later. In 1793, he mortgaged his farm to the Union Bank for $500. The following year, three creditors took him to the Berkshire County Courthouse for debts totaling about 44 pounds. If he did not repay the money within six months, the court commanded the sheriff to “take the body of said Bagg and him commit into our gaol” until his creditors were satisfied. Several weeks later, Phineas gave each of his creditors several acres of the farm as repayment.8

In 1795, he took out another mortgage on his property. Then ten additional creditors to whom he owed a total of $650, including substantial court costs, assessors’ fees and inflated travel expenses, won judgments against him. To repay them, Phineas lost another 62 acres of farmland, the barn and half his house.

The final case, heard in 1797, involved money he owed to tailor John George Randow. Once again, the court ordered that Phineas should be jailed if he did not pay. Phineas did not pay and he did not appear in court. In fact, by that time, he was probably in Canada. Several weeks later, Randow acquired title to a piece of land from Phineas’ farm.

Perhaps these events had convinced Phineas that he could not support his children in Pittsfield. Perhaps he was so distraught, he did not want to try. I do not know whether his extended family members tried to convince him to stay. Meanwhile, it appears he had found a companion who wanted to join him in a new life – or perhaps she persuaded him to go. At some point, he and the children left for Canada, where he lived with Ruth Langworthy, a young woman who had probably accompanied them from Pittsfield. As far as I know, she and Phineas did not marry.

How they chose their destination is another mystery. Probably Phineas knew someone who lived in La Prairie, a town on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River near Montreal, because that is where they ended up.

La Prairie Innkeeper

Phineas received a license to run a tavern in La Prairie on March 15, 1797 and he became an inn keeper.9 La Prairie notary Ignace-Gamelin Bourassa handled six acts for Phineas between September, 1796 and March, 1801, including a lease, an agreement for transportation and a loan guarantee, while notary Edme Henry handled two leases from Joseph Nolin to Phineas Bagg in 1800 and 1803.10 Other notarial records show Phineas purchased land in the La Prairie area in 1805 and sold it in 1813.

Ruth Langworthy gave birth to two children in La Prairie. Daughter Lucie Bagg was baptized in the Catholic parish church in La Prairie on January 11, 1798 by a French-speaking priest and with French Canadian godparents. Son Louis died shortly after birth and was buried April 1, 1800, but Lucie grew to adulthood. I have found no further record of Ruth. By 1809, Phineas had moved across the St. Lawrence and was living on the Island of Montreal, near the mountain. In October of that year, he was appointed overseer of highways for the Ste-Catherine district, an annual unpaid appointment that rotated among parish householders.11

About this time, Phineas may have been a member of the Scotch Presbyterian Church in Montreal.12 A number of Americans were members of the same church. In 1810 he went into partnership with his eldest son, Stanley, as P & S Bagg. They leased a building from landowner John Clark and started a new enterprise as tavern keepers. The Mile End Tavern was in the countryside north of the city of Montreal, at the junction of the only two roads in the area. It must have been a popular spot, especially on days when there was horse racing at the nearby track. Meanwhile Stanley was busy with other business opportunities as a merchant and contractor.

In 1818, when Phineas was around age 67, they closed the business. The following year, Stanley married Mary Ann Clark, their former landlord’s daughter. Perhaps Phineas lived with Stanley and Mary Ann in their house on St. Lawrence Street for the last few years of his life.

When he died in 1823, his funeral service was held at Montreal’s Anglican Christ Church. Phineas Bagg Esquire was probably buried in the old cemetery downtown and his remains later moved to the Bagg famly crypt in Mount Royal Cemetery. Once a debtor threatened with imprisonment, Phineas had become part of a well-respected family.

See also:

“David Bagg’s Life on the Massachusetts Frontier,” Writing Up The Ancestors, June 22, 2018, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2018/06/david-baggs-life-on-massachusetts_22.html

“The Elusive Pamela Stanley,” Writing Up The Ancestors, Sept. 28, 2018, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2018/09/the-elusive-pamela-stanley.html

“Who was Phineas Bagg?” Writing Up The Ancestors, Oct. 11, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/10/who-was-phineas-bagg.html

“Lucie Bagg’s Mother, Ruth Langworthy,” Writing Up The Ancestors, April 15, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/04/lucie-baggs-mother-ruth-langworthy.html

“An Economic Emigrant,” Writing Up The Ancestors, Oct. 16, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/an-economic-emigrant.html.

“The Mile End Tavern,” Writing Up The Ancestors, Oct. 21, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/the-mile-end-tavern.html

“The Life and Times of Stanley Bagg, 1788-1853,” Writing Up The Ancestors, Oct. 5, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/10/the-life-and-times-of-stanley-bagg-1788.html

“Abner Bagg: Black Sheep of the Family?” Writing Up The Ancestors, April 9, 2015, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2015/04/abner-bagg-black-sheep-of-family.html

Notes and footnotes

- The best evidence for his date of birth comes from the record of his burial at Montreal’s Anglican Christ Church. Dated Nov. 3, 1823, it says, “Phineas Bagg esq of Montreal, merchant, died on the 31 day of November [sic] 1823, aged 72 years, and was buried on the 3rd day of November following by me. John Bethune, rector.” (The minister made a mistake on the date of death: it was actually 31 October.)

- A summary of his service record reads as follows: “Bagg, Phineas, Pittsfield.Capt. William Francis’s co.; list of men who marched to Albany Jan. 14, 1776, by order of Gen. Schuyler, and were dismissed Jan. 19, 1776; service, 5 days; also, Lieut. William Barber’s co., Col. Simonds’s regt.; list of men who marched to New York Sept. 30, 1776, and were dismissed Nov. 17, 1776; service, 7 weeks; also, Private, Capt. William Francis’s co., Maj. Caleb Hyde’s regt.; list of men who marched to Fort Edward July 8, 1777, and were dismissed Aug. 26, 1777; service, 7 weeks; also, list of men who enlisted Oct. 26, 1779, to reinforce Continental Army, and were dismissed Nov. 30, 1779.” Ancestry.com. Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution, 17 Vols .[database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1998. Original data: Secretary of the Commonwealth. Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution. Vol. I-XVII. Boston, MA, USA: Wright and Potter Printing Co., 1896. (accessed Jan. 12, 2013)

- Early Vital Records of Berkshire, Franklin, Hampden & Hampshire Counties, Mass. to about 1850 (electronic resource) Wheat Ridge, CO: Search and Research Publ Corp. c2000, p. 22 of sheet 99, F94/p6/M37.

- According to date of birth calculated from age as listed on her tombstone, Polly Bagg Bush was born April 22, 1785 and died Jan 9, 1856. (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/65952231/polly-bush). Stanley Bagg and his brother Abner were both baptized as adults in Christ Church (Anglican) Montreal in 1831. At that time Stanley gave his date of birth as June 27, 1788 and Abner said his date of birth was August 5, 1790, however, this date does not make sense in light of his sister Sopha’s calculated birthdate. “Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968” [database on-line]. Ancestry.com, (www.ancestry.ca, accessed 2 Oct. 2016), entry for Stanley Bagg, 2 April, 1831; citing Gabriel Drouin, comp. Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin. Sophia was probably the youngest of the Bagg children. Dame Sophia Bagg, veuve (widow) Gabriel Roy died Nov. 12, 1860, and at the time was said to have been 69 years, eight months of age. Calculating her date of birth from that, she would have been born around February 20, 1791. (“Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968” [database on-line]. Ancestry.com.)

- United States Census, 1790 Pittsfield, Berkshire, Massachusetts, familysearch.org, results for Phinehas Bagg. “United States Census, 1790,” database with images, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XHKL-1HW : accessed 29 September 2018), Phinehas Bagg, Pittsfield, Berkshire, Massachusetts, United States; citing p. 483, NARA microfilm publication M637, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 4; FHL microfilm 568,144.

- The people of Pittsfield were not great record keepers at this time, however, the Berkshire Family History Association (http://www.berkshirefamilyhistory.org/) has done a good job of transcribing the records that do exist and publishing them in Berkshire Genealogist. The Berkshire Atheneum, the public library in Pittsfield, has an excellent collection of genealogy resources and local history books. I also found some records of Phineas at The New England Historic Genealogical Society library in Boston.

- David P. Szatmary, Shay’s Rebellion: The Making of an Agrarian Insurrection, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1980.

- I copied the microfilmed records of Phineas’ court appearances at the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston in 2011. At that time, I was fairly new to genealogy and did not take proper note of the source. First, I consulted the index to deeds granted by Phineas Bagg in Pittsfield, dated between 1794 and 1797, (character Levy, volume 32, between pages 46 and 111.) The grantees included Williams, Randow, Minteur, Van Schaal, Danforth, Metcalf, Messenger, Gold, Cadwell, Hallister, Noble, Ford and Thayer. Phineas transferred property to these men to cover the money he owed them. These legal documents have been digitized by Familysearch.org and can be browsed under Massachusetts Land Records 1620-1986, Berkshire, Deeds, 1792-1813, vol 31-32, images 438- 442. These online documents are much clearer than the microfilmed version was.

- Historian Donald Fyson told me he came across this license, issued by the Special Sessions of the Peace, in the archives of the City of Montreal when he was working on his PhD.

- Once again, I did this research many years ago and I did not make a full notation of the sources. The indexes to these acts are not online. I remember looking at actual old books at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) on Viger Street in Montreal. My notes mention notary Ignace-Gamelin Bourassa, 1789-1804 La Prairie, microfilmed, reel 2718-2723, Cote CN601,S47; and notary Edme Henry, 1783-1831, Cote CN601,S200.

- Fyson mentioned this in a note to me.

- Rev. Robert Campbell, A History of the Scotch Presbyterian Church, St. Gabriel Street, Montreal, Montreal: W. Drysdale & Co. 1887, P. 252. https://archive.org/details/cihm_00397/page/n1. A section of this book that discusses the large number of New Englanders living in Montreal at the beginning of the 1800s. The author mentions Phineas but incorrectly describes him as Abner Bagg’s brother, rather than his father, so he may have confused Phineas with Stanley.