According to family legend and several published sources,1 my four-times great grandfather John Clark (1767-1827) owned a freehold estate near the cathedral in Durham, England. I imagined a large house surrounded by shady old trees and fields of lush grass.

It probably wasn’t like that at all, but it took me years to discover that.

Clark’s father, a farmer, did not own land. And as a butcher by trade, John did not sound like someone who could either inherit or buy a large piece of property in England. Also, he left for Canada with his wife and young daughter when he was about age 30. If he did have land in England, why would he go to Canada?

I began to wonder whether he owned property in Durham at all.

Then I found John Clark’s will, written in Montreal in 1825.2 It said, “The said testator doth will, bequeath and devise unto his said daughter Mary Ann, her heirs and assigns, the whole of his real estate of all and every nature and description soever, situated and being in the city or town of Durham or in the neighbourhood thereof in England.” In other words, Clark did own property in Durham, but his will gave no clues as to where it was located; thus, I imagined the country house.

Part of my problem was in misunderstanding the term “freehold estate.” This expression simply refers to a property, or real estate, that is “free from hold” of any entity besides the owner.

I also imagined that Clark lived on his own land. When he married in 1794,3 he lived in St. Giles parish, a largely agricultural suburb of the city of Durham, but there is no evidence that he owned property there.

Finding out whether my ancestor really did own property, and where it was, presented three big challenges: the fact that John Clark is a common name, my distance from Durham, and the lack of relevant historical records. Over the years, I have hired three professional researchers to search collections such as land tax records,4deeds, enclosure records and tithe applotment records at the archives in Durham. They added small pieces to the puzzle, but the records themselves are incomplete.

Finally, after 11 years of looking at this question off and on, it has become clear that the exact nature and location of this freehold estate will likely remain a mystery, however, Clark may have owned one or more buildings in the city of Durham.

Durham, a very old city in northeast England, is built on a peninsula surrounded by the meandering River Wear. On top of the hill are Durham Cathedral and Durham Castle. Several bridges cross the river, leading to the market square, and from there, Sadler Street goes up to the cathedral. At one time, Sadler Street was also known as Fleshergate and butchers had their shops there. That may be where Clark owned some property.

A collection of old Durham city deeds notes that a man named John Clark was an occupant of the building at no. 5 Sadler Street until 1796, which was shortly before my ancestor left for Canada.5 He was probably renting or subletting here, though, since his name is not listed among the main parties to the deeds.

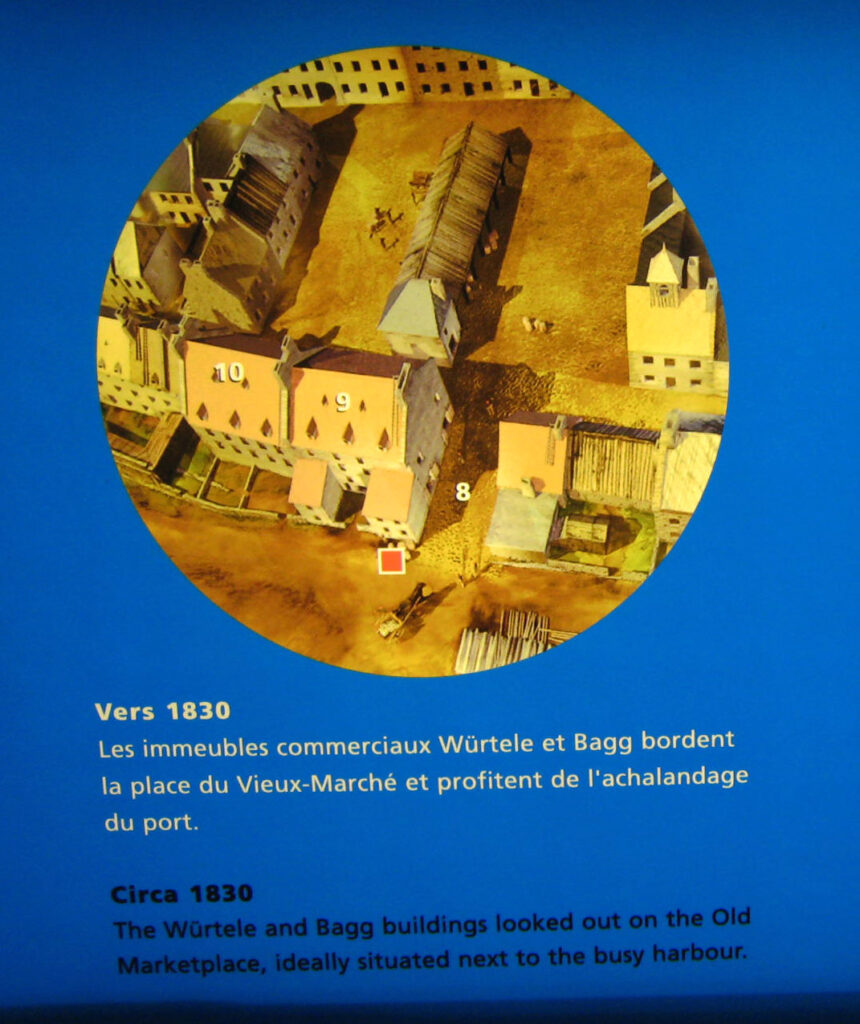

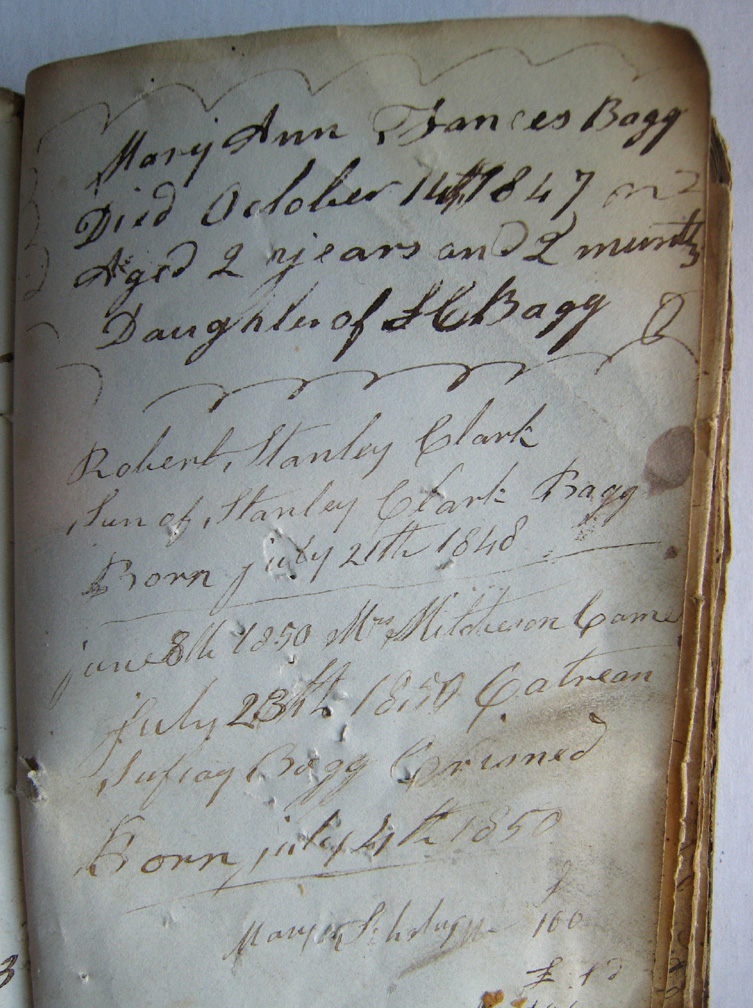

When Clark died in 1827, he left his Durham property to Mary Ann, his only daughter. Mary Ann’s husband, Montreal merchant Stanley Bagg, was executor of the will. Clark also left 13 bequests of 50 pounds each to several of his brothers and sisters in England, and to several of his wife’s relatives.

Two years later, Mary Ann decided to sell the property in Durham.6 It was difficult to manage the property from across the Atlantic, and she could use the proceeds to pay these bequests. William Mitcheson, John Clark’s brother-in-law who lived in London, was appointed an executor of Clark’s will in England. So far, I have not found proof of Clark’s will being probated in England.7

There is strong evidence, however, that the family sold property in Durham in 1842. Mary Ann died in 1835, leaving it to her son, Stanley Clark Bagg (SCB), who was still a minor. Stanley Bagg was the executor of her estate until SCB turned 21 in 1841.

The following summer, Stanley and SCB took a trip together to Durham8 and sold the remaining property. On their return, Stanley recorded the names of the three buyers in a notarized document in which he admitted he had used some of the rental income from the Durham properties for his own purposes. He arranged to repay his son and listed the names of three people who purchased the properties, as well as the name of a Mr. “Bromwell” who had collected the rents.9 The name “Bramwell” was listed in the document regarding no. 5 Sadler Street at the Durham University archives.

Several questions remain: how extensive was the property when Clark first acquired it? Was it sold off bit by bit, or did the properties SCB sold in 1842 represent all of Clark’s real estate? And how did Clark acquire it in the first place? His father left him 70 pounds in 1776,10 when John was nine years old, which was not a huge sum. Perhaps someone helped him invest his inheritance, perhaps he bought the property when he became an adult. Later, in Montreal, he proved to be an astute businessman who invested in property near the city.

Those answers will probably remain a mystery.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Ralph Clark’s 1776 Will,” Writing Up the Ancestors, April 17, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/04/ralph-clarks-1776-will.html

Janice Hamilton, “John Clark of Durham, England,” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 29, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/05/john-clark-of-durham-england.html

Photo credits: Detail of portrait of John Clark, Bagg family collection;

photos of Durham City, Janice Hamilton,

Notes and sources.

- “In Memoriam – Stanley Clark Bagg, Esq., J.P., F.N.S.” The Canadian Antiquarian, and Numismatic Journal: published quarterly by the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Montreal; Vol. 11, No. 2, October, 1873, p. 73. Also, William H. Atherton, The History ofMontreal, 1535-1914, Biographical, vol. 3, p. 406. In this article, Atherton noted that SCB inherited freehold property in County Durham, England, but he wrongly stated that Stanley Bagg was from England. Other authors, including Douglas Borthwick, made the same error.

- “Last Will and Testament of Mr. John Clark of Montreal,” Act of notary Henry Griffin, #5989, 29 Aug. 1825, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, p. 9. 3. England, Durham Diocese, Marriage Bonds & Allegations, 1692-1900, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q21P-XMQK : 29 July 2017), John Clark and Mary Mitchinson, 07 Jun 1794; citing Marriage, Durham, England, United Kingdom, Church of England. Durham University Library, Palace Green; FHL microfilm.

- I searched online the land tax records at the County Durham Records Office for the surname Clark: The name does appear, but I did not find a listing that I could identify as my ancestor. http://www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk/article/10924?SearchType=Param&Variations=N&Keywords=Land%20Tax%20Records&ImagesOnly=N

- 5. Durham University Library, Special Collections Catalogue, http://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/search, results for John Clark, Durham City Deeds, Bundle 22, Sadler Street alias Fleshergate, 5 Sadler Street, east side, Reference: DCY 23/1-34, Dates of creation:1776-1856. The entry says,

- “These premises were described as a burgage [land or property in a town that was held in return for service or annual rent] and shop, with appurtenances, almost throughout. In 1856 it was called a freehold dwellinghouse and shop….The occupants of the property included, initially, John Clark, by 1796 one Haswell ….”

- Annex attached to John Clark’s Last Will and Testament, by notary Henry Griffin, 10 Nov. 1829 and attached to records for lot 110, Saint-Laurent Ward, Montreal, p. 391, Registre foncier du Québec online database.

- I searched online the PROB 11 collection of the National Archives (Prerogative Court of Canterbury and related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers,) but it might be in another record collection. Also, I have searched the online catalogue of the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York, England.

- There are three clues that father and son visited Durham. In 1866, SCB wrote an article called “The Antiquities & Legends of Durham, a lecture before Numismatic & Antiquarian Society of Montreal” in which he recalled his own visit to the cathedral with his father more than 20 years earlier. There is a record in a passenger list of Stanley Bagg and S.C. Bagg travelling from Liverpool to Boston aboard the Acadia. Boston Courier (Boston, Massachusetts, Monday, Sept. 19, 1842, issue 1921;) 19thCentury Newspapers Collection, special interest databases, www.americanancestors.org; accessed 18/04/2019. A search for Mary Ann Bagg in the Durham University Archives online catalogue brings up a result in the Durham Cathedral Library: J.H. Howe Collection. It cites Montreal parish records showing how John Clark was related to Stanley Clark Bagg, and includes an affidavit from Montreal notary Henry Griffin and a note from Charles Bagot, Governor General of British North America, verifying the information. Reference: JJH 11 Dates of creation: 1842 JJH 11/1, 27 April & 9 May 1842. Similarly, there is a note appended to Clark’s will, dated 13 May, 1842, from Charles Bagot, certifying the information; attached to records for lot 110, Saint-Laurent Ward, Montreal, p. 395, Registre foncier du Québec online database.

- “Account and mortgages from Stanley Bagg Esq to Stanley Clark Bagg.” Act #3537, notary Joseph-Hilarion Jobin, 8 October 1842, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. “From ? Summers for sale of property in the neighbourhood of Durham in England, two hundred and five pounds, one shilling and six. From ? Brown, for sale of property in the neighbourhood of Durham in England, four hundred and ninety pounds two shillings. From ? Elliot and son for sale of property in the neighbourhood of Durham in England, seven hundred and ninety-five pounds fifteen shillings. From Wm Bromwell for the rents of the aforesaid property in England in 1841 and 1842, three hundred and eighty-one pounds ten shillings.” In an email dated Jan. 11, 2019, Durham genealogy researcher Margaret Hedley, Past Uncovered, noted, “The names mentioned in the Stanley Bagg document with regard to the sale of property in Durham, I believe may relate to the centre of the city as at least three of the names are (or were) well-known businesses in Durham City.”

- Last Will and Testament of Ralph Clark, Oct. 11, 1776; 1776/C8/2, University of Durham Special Collections Department