with research from the Riverside Historical Society

updated Nov. 11, 2024

Occasionally someone who knows more about one of my ancestors than I do finds my family history blog and gets in touch. That is what happened this summer when Herman Maurer, a member of the Riverside Historical Society in New Jersey, reached out to tell me that my ancestor had founded his town.

Three years ago, Herman wrote a book called Progress to Riverside: A Story of Our Town’s Past to mark Riverside Township’s 125th anniversary. In the course of his research, he ran across 19th century Philadelphia real estate agent Duncan M. Mitcheson.1

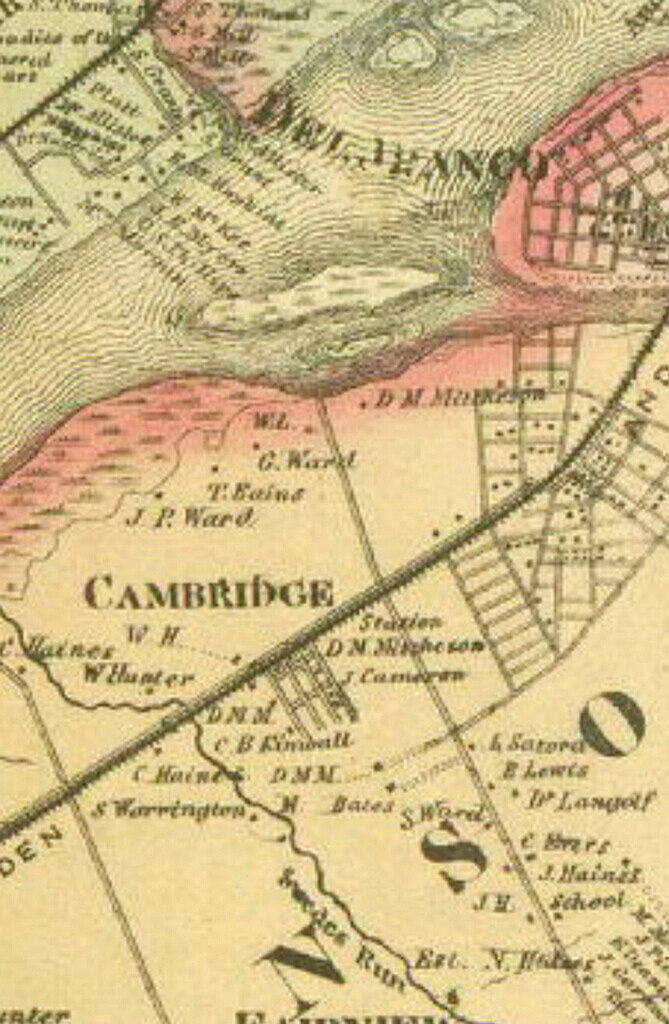

Riverside, New Jersey is a suburban township located across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. In the early 1850s, Duncan and his brother McGregor J. Mitcheson purchased property next to Riverside and subdivided it into cottage lots. This area became the village of Cambridge, located in the Township of Delran. Duncan planned the street layout, including today’s busy Chester Avenue. Front Street, Brown, Main and Arch Streets still carry the names that Duncan chose 170 years ago.

Numerous Cambridge deed transfers recorded in the local county clerk’s office between the 1850s and mid-1880s, with the signatures of both Mitcheson brothers on them, convinced Herman that Duncan and his brother McGregor were the primary developers of the village of Cambridge.

This was a surprise to me since I knew very little about Duncan. Now it became clear that he was a successful businessman who embraced modern ideas at a time of rapid changes in society.

Duncan McGregor Mitcheson (1827-1904) was the middle child of Robert Mitcheson and Mary Frances McGregor. Born in northern England and in Scotland, they were married in Philadelphia around 1818. Duncan’s older sister, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, was my two-times great-grandmother. The Mitcheson family lived in Spring Garden, in the northern part of Philadelphia. The family’s home was large and, after their parents died around 1860, Duncan’s older brother, Reverend Robert M. Mitcheson, and his wife and children lived there. Duncan lived with them until his brother died in 1877. In the 1880 census, when he was age 53, Duncan appears to have been staying in a rooming house. Later Philadelphia city directories show that he lived on Spruce Street, near the old part of the city, and had an office nearby on Walnut Street. He never married.

Like his two brothers, Duncan attended the University of Pennsylvania, but unlike them, he did not graduate.3 He dropped out in 1842, at the end of his second year. University attendance was rare then: there were only 26 students, all male, in Duncan’s freshman class.

Duncan began his career as a merchant, but an 1861 Pennsylvania business directory identified him as a conveyancer: someone who draws up deeds and leases for property transfers. He was listed as a real estate agent for most of his career.

The Riverside Historical Society’s research revealed that Duncan invested $5000 in land in New Jersey, with an initial purchase of 80 acres, in 1853. He and his brother then formed a real estate partnership to develop the village of Cambridge. An advertisement for these building lots appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper Public Ledger on March 24, 1853. The lots were “located on the Camden and Amboy Railroad, about one mile below Rancocas Creek and the Town of Progress and within a quarter of a mile of the River Delaware, upon a very healthy, dry and level site that will require no filling up, nor grading and can be reached in about half an hour from the Walnut Street Wharf.”

The lots were advertised at the “remarkably low rates” of $25 and $30 each. The $30 lots were 20 feet by 100 feet, while the $25 lots were slightly smaller. A few larger lots were available at $60 and $100 each.

On November 4, 1854, another ad in the Public Ledger noted that the Cambridge lots were near the water, opposite the splendid riverside mansions of Philadelphia’s 23rd Ward. Duncan also reassured potential buyers that the lots were a safe investment. “From the continued increase of the population of Philadelphia, and the consequent increased demand for Houses and Lots, and as well as from the fact that thousands now living in this city could not only have more room, enjoy better health, but live less expensively at Cambridge.”

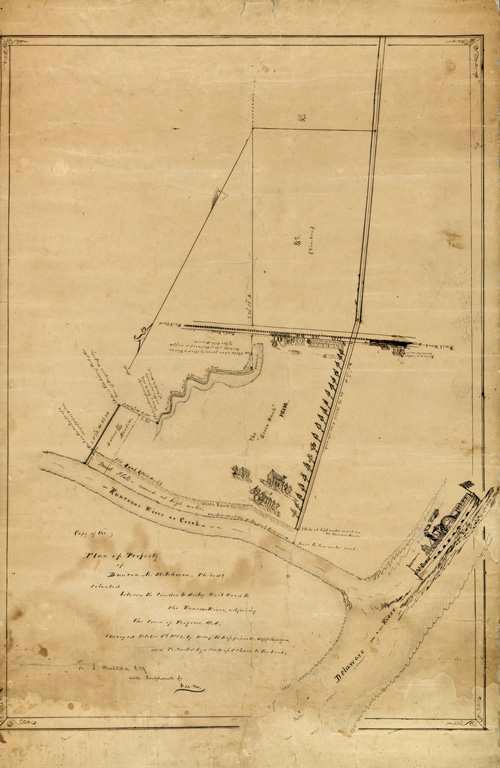

Duncan also owned farmland on three sides of Cambridge, and he was one of the larger landowners in the town of Progress in the 1850s. In January, 1854 he purchased 180 acres of vacant land for $15,000. That property, located between Rancocas Creek, the railroad, Chester Avenue and Tar Kiln Run, was known as Green Bank Farm, or Duncan M. Mitcheson’s Model Farm.

This was a period of technological and scientific innovation. The Great Exhibition, held in London, England in 1851, had showcased developments in many fields, including agriculture. These advances were badly needed: food production had to become more efficient to feed growing urban populations. Duncan’s model farm may have featured agricultural innovations such as a McCormick reaper that could rapidly harvest large quantities of crops. And perhaps Duncan was a member of the Model Farm Association, formed in 1860 to establish a model farm, botanic garden and agricultural school in Pennsylvania.

In the spring of 1854, Duncan purchased another 80 acres of vacant land for $6000, extending Green Bank Farm past the railroad tracks. In addition, he, or possibly his brother, owned a nearby property named Rob Roy Farm, after the famous Scottish outlaw and folk hero Rob Roy McGregor.

How the Mitcheson brothers acquired the funds to buy so much land is not known, but their father owned properties in England and in Philadelphia. Robert Mitcheson senior died in 1859 and in his will, he forgave an $8000 mortgage he held on Duncan’s farm.

In 1859, the Drake Well, the first commercial oil well in the U.S., was drilled in north-western Pennsylvania. That well sparked the first petroleum boom in the United States, creating a wave of investment in drilling, refining and marketing. Duncan saw an opportunity to make money. In February, 1865 he placed the following ad in the Philadelphia Inquirer: “OIL LANDS FOR SALE—located in Venango and Clarion Counties (Pennsylvania). Companies are about to be formed, secure choice lands by addressing or writing to: Duncan M. Mitcheson, real estate office at the northeast corner of Fourth and Walnut Streets, Philadelphia. Also 1,000, 20,000 and 50,000 acres in West Virginia.”

He placed another ad a month later: “CHOICE Oil Tract…Eighty Acres. For sale in fee simple lots situated on the Bennyhoff Creek, Venango County, of which the greater part is boring grounds. This eighty-acre tract will be divided to suit and sold fee simple, with unquestionable titles…” In July, 1866 Duncan advertised another speculative deal in the Philadelphia Inquirer: 1250 interests, valued at $100 each, in The Virginia Gold Mining Company of Colorado. The company’s property was located near Central City, Colorado, founded in 1859 during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush.

In 1893, when he was 70 years old, Duncan sold almost 1000 vacant building lots in Cambridge for the sum of one dollar to his deceased brother McGregor’s two grown children, Joseph McGregor Mitcheson and Mary Frances Mitcheson. During the first two decades of the 20th century, they sold many of the Cambridge properties to families who had recently emigrated from Poland.

Joseph, a bachelor, was a Philadelphia lawyer and a commander in the U.S. naval reserve. Mary Frances married accountant Arthur L. Nunns in 1904. The couple were childless and when she died in 1959, at age 84, she gave a million dollars to the Protestant Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. It was the largest bequest it had ever received.4 During my 2013 visit to Philadelphia, the head of St. James School, a tuition-free, private Episcopalian middle school, told me that gift Is still benefiting the community.

As for Duncan, the 1900 census showed that he had retired. He died in 1904 and was buried, along with his parents and other family members, at St. James the Less Episcopal Church Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Note: The Duncan M. Mitcheson Green Bank Farm map, dated 1853, was provided by the Riverside Historical Society. The society’s copy of this map was conserved through a 2023 grant funded by the Burlington County Board of Commissioners.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Robert Mitcheson, Philadelphia Merchant”, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 1, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/03/robert-mitcheson-philadelphia-merchant.html

Janice Hamilton, “The MacGregors: Family History or True Story?” Writing Up the Ancestors, March 21, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/03/the-macgregors-family-legend-or-true.html

Janice Hamilton, “Philadelphia and the Mitcheson Family” Writing Up the Ancestors, Nov. 22, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/11/philadelphia-and-mitcheson-family.html

Janice Hamilton, “The Great Central Fair of Philadelphia, 1864”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct. 31, 2024, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2024/10/the-great-central-fair-of-philadelphia-1864.html

Sources:

- Herman Maurer, Progress to Riverside: A Story of Our Town’s Past, Riverside Historical Society Inc. 2020, p. 13.

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, City Directory 1889, entry for Mitcheson, Duncan M., Ancestry.com, citing U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 (online database), accessed Oct. 1, 2024.

- University of Pennsylvania, 1894. entry for Duncan MacGregor Mitcheson. Ancestry.com, citing US. College Student Lists, 1763-1924 (online database), accessed Oct. 1, 2024.

- The New York Times, May 6, 1959.