Philadelphia lawyer McGregor J. Mitcheson (1829–1886) had a reputation as a passionate and eloquent defender of his clients’ interests in the courtroom, so it comes as no surprise that he was also a persuasive fundraiser. In 1864, he was one of many volunteers who helped to raise money to improve sanitary conditions, food and medical care for government soldiers during the American Civil War.

When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, thousands of men signed up to fight for the Union army. Soon, however, the filth and poor diets in the camps where the soldiers were housed led to outbreaks of disease. People realized that the government was not equipped to shelter and feed so many soldiers.

Civilians in the northern states responded by founding the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) in the summer of 1861, as well as other charitable relief organizations. These groups raised money for the Union cause and distributed supplies, including food, clothing and bandages, to military camps and hospitals. A branch of the USSC was set up in Philadelphia by some of the city’s leading male citizens, while the women set up their own organization to receive donations from church groups and other small, local aid societies2.

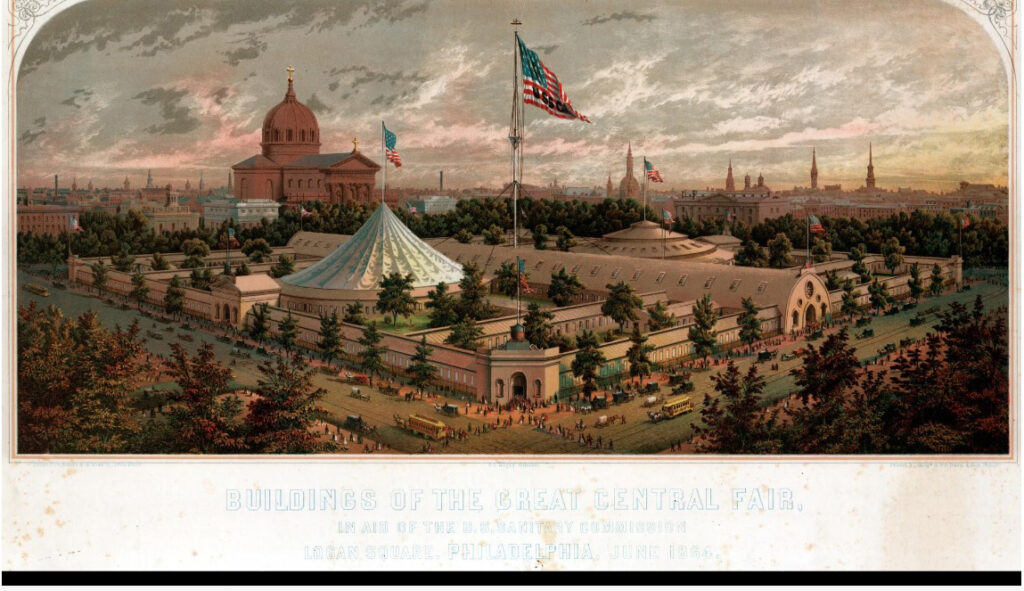

These organizations held a variety of fundraising events, including concerts, plays and floral fairs, but the biggest and most successful event In Philadelphia was the Great Central Fair. It was held for 21 days in June, 1864, at downtown Logan Square. Volunteers built a vast central hall featuring Gothic arches, outbuildings, interconnecting corridors and a 216-foot flagpole. A range of donated goods were for sale including fine arts, lingerie, umbrellas and canes, arms and trophies and children’s clothing, while available services included a horse shoe machine and a button-riveter.

A number of northern cities hosted sanitary fairs between 1863 and 1865, but the only one that raised more money than Philadelphia was New York City. In total, the Philadelphia Great Central Fair raised more than a million dollars – $20 million in today’s money.

This huge endeavor required many hours of organization by hundreds of volunteers. An executive committee oversaw dozens of smaller departments and committees that were in charge of soliciting contributions of goods, money and services from members of every trade, profession and business in the city.

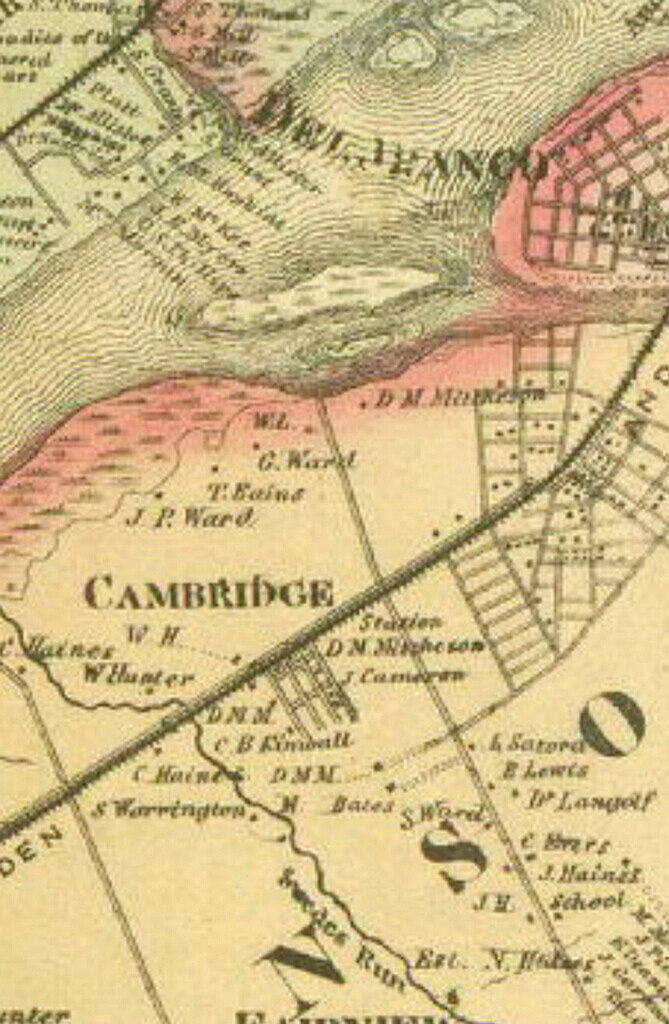

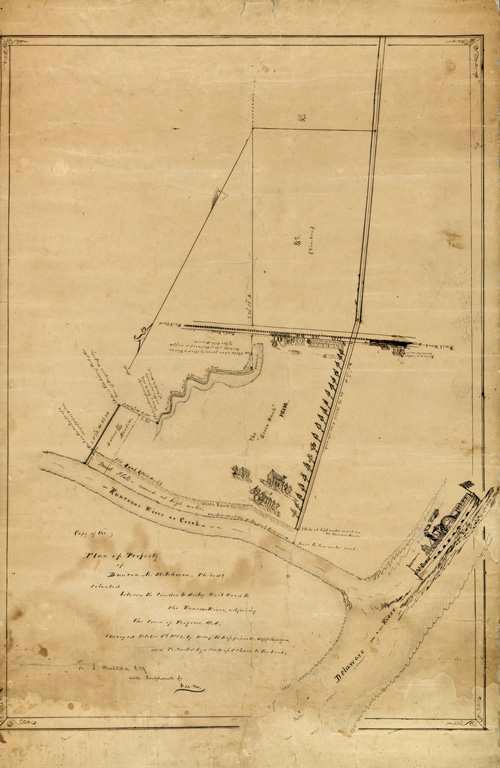

My three-times great-uncle McGregor J. Mitcheson dedicated many hours to the cause as secretary of the fair’s Department of Labor, Income and Revenue. Involvement in that department was something of a family affair: at one time, McGregor’s brother Duncan M. Mitcheson was assistant treasurer, and his sister Mary F. Mitcheson was a member of the women’s committee. McGregor was also chairman of a hard-working sub-committee, the Committee on Organization.

The Department of Labor, Income and Revenue was one of the busiest of the Sanitary Fair organization, and it succeeded in raising nearly a quarter of a million dollars, or one-fourth of the fair’s proceeds. Its goal was to raise donations equivalent to the wages of one day’s labor from working people in every branch of industry, one day’s income from their employers, and one day’s revenue from all corporations. Railways and coal mining companies proved to be the most generous donors. This committee also had a large table at the fair where a variety of goods were sold, bringing in $7228.

Committee members personally visited company worksites such as iron works and large mills. Owners would tell their employees to stop work and call them together to hear a speech about the need to help the soldiers. Most employees were so inspired that they agreed to donate a full day’s wages, and their employers also gave generously. Official fair historian Charles J. Stille credited this success with the fact that the organizing committee had nothing to do with partisan politics, and had no specific religious affiliations. Everyone was free to give or not to give.

The committee raised funds in Philadelphia, in smaller Pennsylvania cities such as Bethlehem, Harrisburg and Reading, in rural parts of the state and in neighbouring New Jersey. Members of this committee were so hard-working that it acquired the nickname the laborious committee.

Stille singled out McGregor J. Mitcheson for his hard work. “Through spirited explanatory addresses by Mr. Mitcheson, at the invitation of the proprietors of the leading establishments, six eight, and even twelve manufacturers have been thus visited by the officers and committee; the works stopped, the people collected and addressed, as we have stated, within one day.”3

McGregor also played a memorable role in the fair’s closing ceremony. A large crowd turned out on the evening of June 28 to watch as members of the fair’s executive committee marched onto a platform in the square. The bishop offered a prayer of thanksgiving, then McGregor J. Mitcheson led the singing of the Doxology,4 a hymn of praise. After that, McGregor invited the crowd to sing the Star-Spangled Banner, and finally the crowd broke into an enthusiastic rendition of Yankee Doodle.

Photo Sources:

Queen, J. F. (1864) Buildings of the Great Central Fair, in Aid of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, Logan Square, Philadelphia, June. United States of America Philadelphia Pennsylvania, 1864. Philadelphia: P.S. Duval & Son Lithography, -07. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670451/

Cabinet card photo by William Notman, Montreal. #70199. Bagg family collection.

Notes and Sources

- McGregor J. Mitcheson (born Joseph McGregor Mitcheson) was the youngest son of English-born merchant Robert Mitcheson and his Scottish-born wife Mary Frances McGregor. His older sister, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, was my direct ancestor. McGregor grew up in Philadelphia and practised law there for many years. He married Ellen Brander Alexander Bond, a widow, in 1869, and they had three children.

- Kerry L. Bryan, “Sanitary Fairs”, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/civil-wr-sanitary-fairs/, viewed Oct. 25, 2024.

- Stille, Charles J. Memorial of the Great Central Fair for the U.S. Sanitary Commission Held at Philadelphia held at Philadelphia, June 1864. Philadelphia: United States Sanitary Commission, 1864. https://books.google.ca/books?id=csFNAQAAIAAJ&dq=inauthor:%22Charles+Janeway+Still%C3%A9%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s&redir_esc=y&hl=en, viewed Oct. 30, 2024, p. 43

- The Doxology is a four-line hymn often sung during church services The version sung at the fair’s closing ceremony: Praise God, from whom all blessings flow; Praise him, all creatures here below; Praise him above, ye heavenly host; Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Amen.

This article is simultaneously posted on the collaborative blog Genealogy Ensemble, https://genealogyensemble.com.