I have taken advantage of all the extra free time at home over the past year to write a family history book about my father’s ancestors. It has been the perfect pandemic project, but now it is almost time to launch it into the world.

This book brings together the many blog posts I have written about my father’s extended family over the past eight years for my personal family history blog, Writing Up the Ancestors, and for the collaborative blog Genealogy Ensemble. As someone once told me, a blog is a good cousin catcher, and indeed, blogging has allowed me to connect with cousins I never knew I had. Also, I got a lot of the research done and written up in small bites. But the stories about the Hamilton and Forrester families (my paternal grandmother was a Forrester) jump all over the place on the blog; in the book, they are in historical sequence and geographical context.

A book that you can hold in your hands and store on your bookshelf for years also feels more permanent. People read a blog post, then jump to the next shiny object on the Internet. You might only read part of a book, or look at the photos, but you can keep it for a long time and pass it on to the next generation. I’m dedicating this book to my grandchildren, in the hope that one day, maybe 50 years from now, they will sit down and discover all the astonishing things their ancestors risked and achieved.

I have called this book Reinventing Themselves: a History of the Hamilton and Forrester Families. These people reinvented themselves several times. Most male members of the immigrant generation grew up in lowland Scotland where they were weavers, stonemasons, tenant farmers and carpenters. When they landed in Upper Canada around 1830, they had to reinvent themselves as farmers in an unfamiliar climate. Members of the next generation retained most of their Scottish customs and religious beliefs, but moved on to a new landscape as they became grain famers on Canada’s western prairies. Their sons and daughters were the first to give up farming and forge careers in the city.

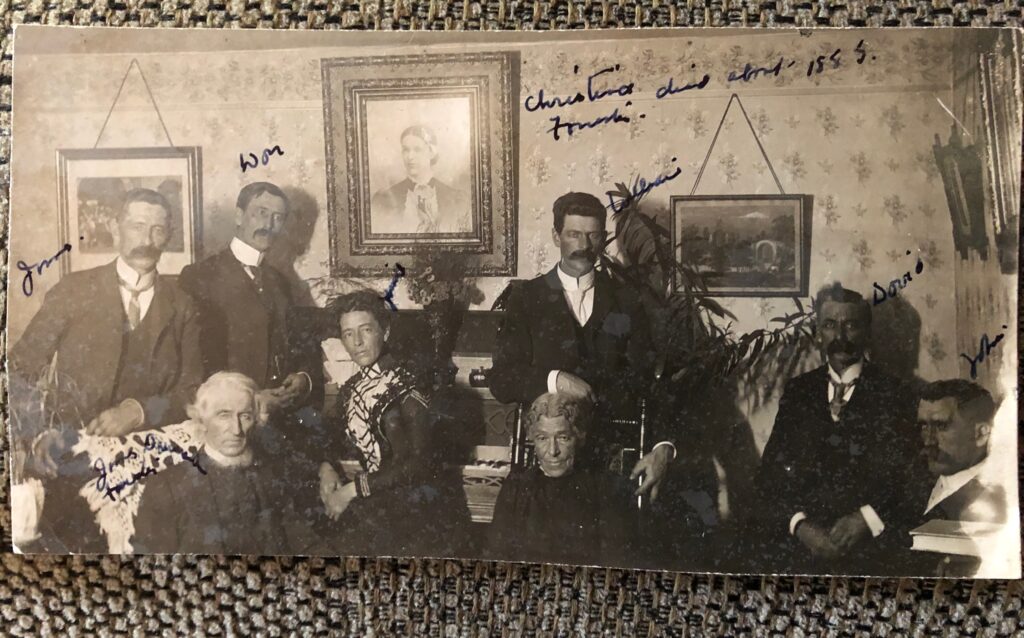

My grandmother’s family lived on a farm in southern Manitoba. Here are her grandparents, James and Janet Forrester, both of whom were born in Scotland and came to Hastings County in Upper Canada as children in 1833. Their children were James, Don, Jennie, William, David and John (known as Jack) and a picture of their deceased daughter, Christina, in the background. This photo was probably taken in 1900 when James and Janet celebrated their golden wedding anniversary. Photo courtesy Linda Klassen.

Many Canadian pioneer families followed similar paths, so what makes this story special? Part of its value is that it does represent the experiences of many 19th century immigrant families.

Luckily, many accounts of my ancestors’ unique experiences have survived. In a letter to his father back in Scotland, immigrant Robert Hamilton (1789-1875) recounted the family’s voyage across the Atlantic. Fifty years later, his granddaughter Maggie Hamilton (1862-1886) wrote a letter from Saskatoon in which she described baking bread for the government soldiers following the North West Rebellion in 1885. Fast forward another eighty years and Charles Forrester (1889-1984) wrote a book about life on the farm near Emerson, Manitoba, from hauling water for the livestock to singing Scottish ballads at family gatherings.

I used to envy people who were members of various ethnic groups. They seemed so exotic, while my ancestors seemed pretty boring. But writing this book has helped me appreciate the values these Scots brought with them: their deep sense of community and their competitiveness, their love of books and learning, their love/hate relationships with alcohol, and their strong work ethic.

The book also has its share of surprises, from the discovery of my great-grandmother’s illegitimate birth and the story of brothers who were globe-trotting plant collectors to the death of my father’s twin in the 1918 flu pandemic and my grandparents’ subsequent investigations into psychical phenomena.

The research, writing and editing are done. It’s too late now for changes, although I will always be itching to tweak something. The manuscript and many, many photos are in the hands of a book designer. I’ll let you know soon when and how to get a copy.

This article is also posted on the collaborative blog Genealogy Ensemble.