The Seigneurie of Milles–Îles, part one

It must have been a happy wedding. For a girl from relatively humble American roots to marry the owner of one of Quebec’s vast seigneuries, this must have seemed like a wonderful match. And the groom had recently lost his parents, so family members were no doubt pleased to see him marry.

Unfortunately, there was no fairy-tale ending to this story.

The bride was Sophia Mary Roy Bush. She was born Sophia Mary Bush around 1815, the daughter f William Bush, farmer, of West Haven, Vermont, and Polly Bagg Bush. (Sophia’s grandfather, Phineas Bagg (c. 1750-1823), was our common ancestor.) Her family struggled financially, so Sophia had come to Montreal to live with her wealthy aunt and uncle, Sophia Bagg and Gabriel Roy, who had no children of their own.

The groom was Louis Charles Lambert Dumont, born in 1806, the son of Eustache Nicolas Lambert Dumont. Eustache Nicolas had been co-seigneur of Milles-Îles, a judge, militia officer and politician, but he had accumulated crippling debts running the seigneury, and had fallen out with his sister because their father had left them unequal shares of the seigneury.

The Dumont family had been seigneurs of Milles-Îles since 1743. They owned a vast area of wilderness and fertile farmland northwest of Montreal. According to traditions that went back to the time of New France, the habitants, or farmers, paid rent annually to the seigneur, cleared the land and grew their crops. The seigneur built grist mills, saw mills and roads. In 1770, the Dumonts donated land for the construction of a Catholic church and the village of Saint-Eustache grew up next to it. They later built their seigneurial manor house near the church.

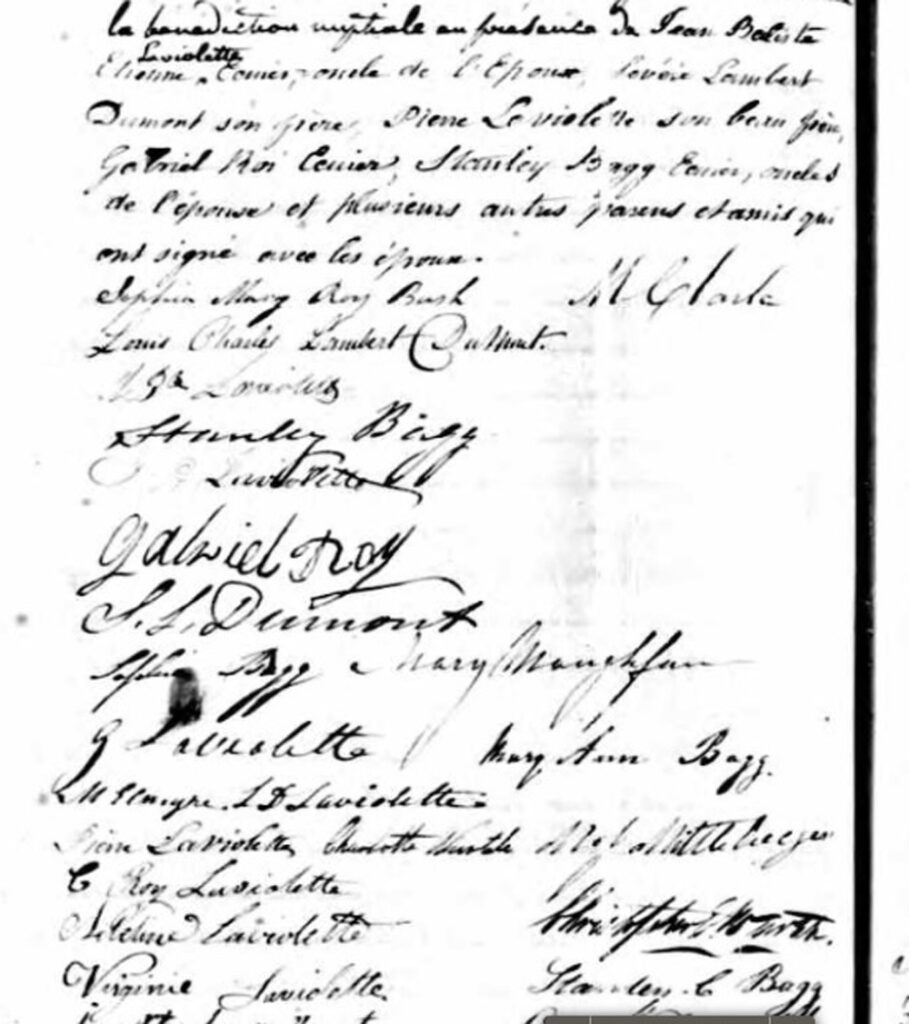

Louis Charles’ and Sophia’s wedding did not take place in Saint-Eustache; it was held at the parish church in Saint-Laurent, where the Roy family lived, on September 22, 1835. Saint-Laurent is now a suburb of Montreal, but at that time it was a rural area on the Island of Montreal.

On the bride’s side, no less than eight family members signed the parish record book. Her parents’ names did not appear, so they had probably been unable to come to Montreal for the wedding, but Sophia Bagg and Gabriel Roy signed, as did the bride’s uncle Stanley Bagg, his 15-year-old son, Stanley Clark Bagg, and his mother-in-law, Mary Mitcheson Clark. Sophia’s and Polly’s other brother, Abner Bagg, seems to have been absent, but his wife, Mary Ann Mittleberger, did sign the register.

Among Louis Charles’ relatives who signed the book were his sister Elmire, her husband, Pierre Laviolette, and seven other members of the Laviolette family. The groom’s brother, Louis Sévère Dumont, was also present. Their father had died that April, their mother the previous year, and their twelve other siblings were deceased.

The newlyweds went to live in the seigneurial manor house in Saint-Eustache, but their life was not easy. Louis Charles was learning how to administer the debt-ridden seigneury, arguing over money with his brother and fighting off court challenges over the property by his aunt. Then the couple’s first-born child, a daughter, died in 1837, shortly after her first birthday.

Meanwhile, social and political tensions had been increasing in Lower Canada. When the government refused to approve reforms, an armed rebellion broke out. On December 14, 1837, some 2000 government troops attacked the Patriotes, or rebels, barricaded inside the church at Saint-Eustache, killing some 60 people. The troops burned the church, the convent and much of the village, including the Dumont manor house.

Fearing trouble, Louis Charles and Sophia had left Saint-Eustache for Montreal in November. When they returned in the spring, they moved into a smaller house down the road. Their second child, Marguerite Virginie Lambert Dumont, was born there on August 21, 1838.

On June 27, 1841 Sophia died suddenly, age 26. The body of Louis Charles, 36, was discovered in his house on November 1. His brother, Louis Sévère, died eight weeks later, age 31. None of the accounts of this family’s history explains these deaths, and several historians seem to suggest that these events were suspicious. Three-year-old Virginie was now an orphan and a future heiress.

This story was edited August 13, 2015 to change the title.

See also: “Marguerite Virginie Globensky,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 27, 2015 https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2015/01/the-story-of-marguerite-virginie.html

Notes

I do not know Sophia’s exact birth date, but the priest who buried her on July 1, 1841 wrote that she was age 26 years, three months at the time of death, so she must have been born around the beginning of April, 1815.

Written accounts refer to Sophia Mary as Gabriel Roy’s adopted daughter. So far I have not found legal adoption records, though there may be some. The parish marriage record simply refers to her as the daughter of William Bush and Polly Bagg. Sophia’s birth parents were Protestant, so in 1827, Sophia was baptized Catholic. That church records says she added the name Roy at that time, and it refers to Gabriel Roy and Sophia Bagg as her sponsors. She was age 12 at the time and signed the parish record book herself.

Polly, Sophia, Stanley and Abner Bagg were born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in the 1780s to Phineas Bagg and his wife Pamela Stanley. The Bagg and the Stanley families had lived in Massachusetts and Connecticut since the mid-1600s.

Saint-Laurent parish records show that Sophia Bagg and Gabriel Roy did have one child: Edouard Gabriel Roi, born in 1812, died in 1815.

On the Bagg side, one important family member was missing from the marriage register: Mary Ann Clark, wife of Stanley Bagg, had died the previous year. The Mary Ann Bagg who was present was Abner Bagg`s daughter. Another name on the marriage record was Mary Maugham, who was related to Mary Mitcheson Clark.

There are BMD records for these families in the Drouin Collection on Ancestry.ca, but indexing mistakes and legibility issues make them hard to find. Search for Dush instead of Bush, and for Dumont, not Lambert Dumont. Also, Sophia’s name appears in the records as both Mary Sophia and Sophia Mary, though in French-speaking Quebec she would have been called Marie Sophie.

Members of the both the Dumont and Globensky families fought on the government side at the Battle of Saint-Eustache. Sophia`s relations were also involved in putting down the rebellion. Her uncle Stanley Bagg was a major in the 1st Battalion Loyal Montreal Volunteers, and according to a family story, his son, Stanley Clark Bagg, age 17, was an ensign bearer at the Battle of Saint-Eustache, but I have not yet confirmed that.

There are many websites and books concerned with the individuals and events of the Battle of Saint- Eustache. Among those I consulted were the entry on Nicolas-Eustache Lambert Dumont in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (www.biographi.ca/); Elinor Kyte Senior’s Redcoats and Patriotes, The Rebellions in Lower Canada 1837-38, Stittsville, ON: Canada’s Wings, Inc. 1985; André Giroux, Histoire du territoire de la ville de Saint-Eustache, tome 1, L’époque seigneuriale 1683-1854, Québec: Les Éditions GID, 2009; an article about the Dumont house written by the Société de généalogie de Saint-Eustache, http://www.sgse.org/maisons/chron/a00226.html; and an online article by André Giroux, Les héritiers d’Eustache-Nicolas, http://www.patriotes.cc/portal/fr/docs/revuedm/06/revuedm06_6.pdf.