William the Conqueror must have thousands of descendants, but it seems quite a coincidence that I had thoroughly researched his life before I was aware there was a direct connection between us.

I learned about that connection from Gary Boyd Roberts, Senior Researcher Emeritus of the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) and author of many books, including The Royal Descents of 600 Immigrants to the American Colonies of the United States. A half-hour meeting with Roberts was part of a weekend research event at the NEHGS that I attended a few years ago.

Roberts was a bit intimidating. He insisted I not look at my notes, but look at him, and he was baffled that I was interested in my ancestors’ lives. For him, the births, marriages and deaths were all that mattered. He seemed to have memorized the lineages of just about every family in colonial New England, and he indicated the pages of the family history books I should photocopy. When he learned I am Canadian, Roberts remarked that I have a “nice chunk of Yankee.”

He then pointed to the name Margaret Wyatt on my family tree and stated, “she was of royal descent.”

That royal ancestor was King Henry I, but the name did not ring any bells until I returned home and looked up Henry I on the Internet. Then I realized that Henry was the youngest son of William the Conqueror, about whom I had written a book!1 The book told the story of how William, Duke of Normandy, became King William I of England almost thousand years ago. Titled The Norman Conquest of England, it is one of several non-fiction books I have written for children.

William’s own ancestry was actually Viking: the Normans were people from Scandinavia who began raiding northern France around 800 A.D. In 911, William’s ancestor Rolf the Viking took control of the area that became known as Normandy.

William was born in Normandy around 1028, the illegitimate son of Duke Robert I of Normandy and a young woman named Herleve, who was probably the daughter of a tanner. Even as a child, William had many rivals, but eventually he succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy.

In 1066, he famously crossed the English Channel and defeated the English troops at the Battle of Hastings. He was a powerful and violent man, and a good military commander. The story of how William the Conqueror evaded his enemies and invaded England is full of intrigue and coincidences. After writing about these events, my husband and I toured northern France, including Bayeux, home of the Bayeux Tapestry that illustrates the Norman Conquest. Little did I know at the time that William was one of my ancestors.

After William I’s death in 1087, his son William Rufus became king of England. Following the death of Rufus, William the Conqueror’s youngest son became King Henry I. Henry, who had been born in England, ruled from 1100 to 1135. Well educated, decisive and energetic, he was known as the Lion of Justice.

Henry married Matilda of Scotland, but the line of descent that leads to America was through an unnamed mistress. Their illegitimate child was Robert of Caen, 1st Earl of Gloucester. At generation 19 came Margaret Wyatt ( – c. 1675).2 She married Matthew Allyn (1605-1671) in Devonshire, England in 1626/27 and a few years later they sailed across the Atlantic, settling in Hartford and later in Windsor, Connecticut.

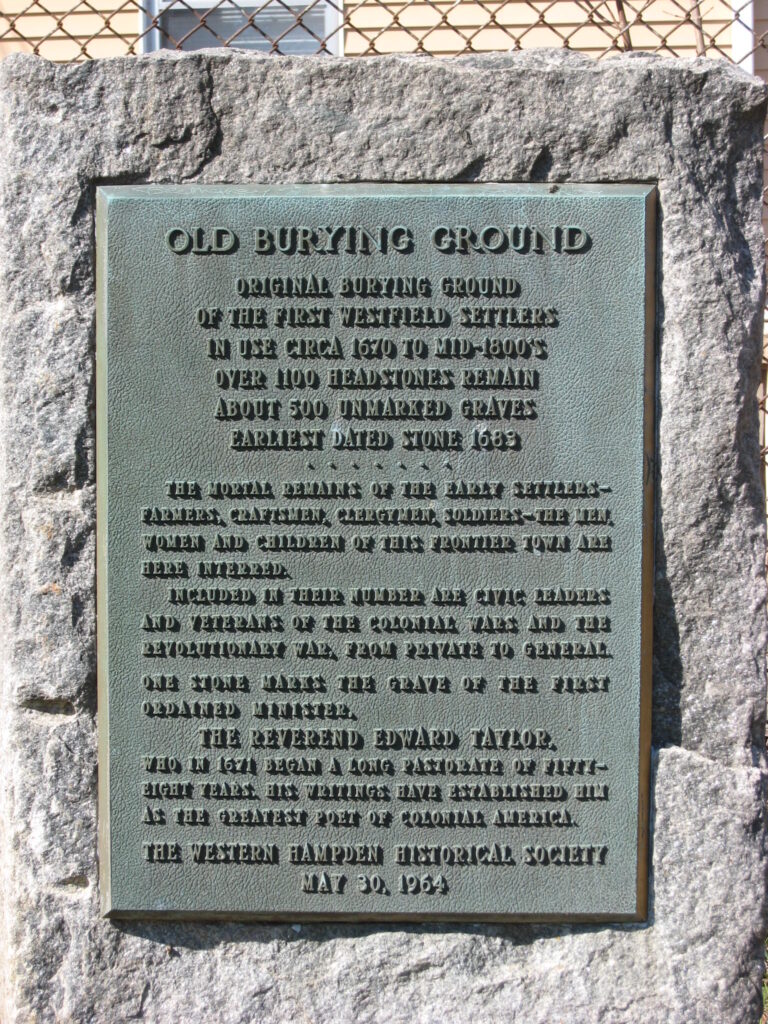

From there, my line goes through their daughter Mary Allyn who married Benjamin Newberry; their daughter Mary Newberry who married John Moseley; their son Consider Moseley, who married Elizabeth Bancroft; and their daughter Elizabeth Moseley who married David Bagg in Westfield, Massachusetts. Their son Phineas Bagg, my four-times great-grandfather, left New England for Montreal, Quebec with his children around 1795.4

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Considering Consider Moseley,” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 16, 2018, writinguptheancestors.ca/2018/05/considering-consider-moseley.html

This article is also posted on https://genealogyensemble.com

Sources.

- Janice Hamilton, The Norman Conquest of England, Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books, 2008.

- Gary Boyd Roberts, compiler, Ancestors of American Presidents,2009 Edition. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2009, p. 408.

- The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England 1620-1633, Volumes I-III. (Online database: AmericanAncestors.org, New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2010), (Originally Published as: New England Historic Genealogical Society. Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England 1620-1633, Volumes I-III, 3 vols, 1995) https://www.americanancestors.org/DB393/i/12107/42/235171345

- Janice Hamilton, “An Economic Emigrant,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct. 16, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/an-economic-emigrant.html